Some lawyers attending a Sierra Club Board meeting in California might do a side trip to Hawaii, or San Fransisco. Jim Dougherty’s agenda is a little bit different. While he continues to work as a lawyer, his work as a photographer is gaining notice. And his side trip from a recent Board meeting to hike for a week in Utah could result in a solo exhibition at an art gallery.

“I don’t fly in airplanes for pleasure or photography, in order to reduce my carbon footprint,” Jim said recently. “And I haven’t used A/C for 20 years at home. My photo expeditions are taken only in conjunction with eco-business. I take side-trips to Yosemite or stop in Utah on the way back. My adult life has been devoted to defending nature… I take pictures to remind people of Mom Nature’s majesty – and to inspire them to step up to their responsibility to defend her.”

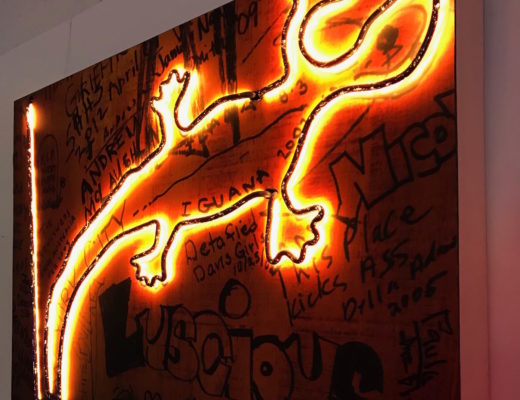

Photograph by conservation photographer Jim Dougherty. All rights reserved.

Dougherty is a heavyweight as a litigator (“I’ve done more sea turtle litigation than any other American lawyer,” he said) but during a quick tour of the Sierra Club headquarters last week, Dougherty paused to flip through a special edition book printed on the occasion of the Sierra Club’s centennial and paid special attention to the photographs. “I most appreciate,” he says, “the photos that say to me ‘This place should be enjoyed or protected.’”

The Sierra Club has a long history with conservation photography, a genre that captures the beauty of nature as an advocacy tool. Ansel Adams took photographs for the Sierra Club, and served for years on the Board of Directors. Still today the Club supports a conservation photography award in his honor.

Dougherty continues in Adams’ tradition and the results are similarly majestic portraits of American terrain, at times surreally so. A dune in Death Valley lightly touched by the footsteps of a bird. Clouds perched between massive stone faces in Yosemite.

Taking the photographs requires immersion in the natural world, something you might sense as your eyes linger in the images. “The longest I’ve hiked for an image is two days out and two days back,” Dougherty said. “I wanted to take a shot of the sun setting on the Tetons from the west side, not the east. To do that you walk about 7 miles each way, but if you’re going to catch the setting sun you have to spend the night. That ended up being a 4-day, 30-mile backpack to get that one shot.”

For Dougherty, that kind of story is not uncommon. “Last February,” he recalled, “I hiked the 2.6 mile trail from the west side of Island-in-the-Sky, in Canyonlands National Park, to shoot the False-Kiva cave. I nailed the sunset shot and decided to wait to try and get a starry-sky image. I’d brought a sandwich and a liter of water, just in case. But the walk back, in the dark, proved treacherous. The trail was snowy and rocky and steeply uphill. At one point I got turned around and had to re-locate and at another point I slipped on a snowy rock and slid about 8 feet on my arse – with no damage but it was scary in the dark, and I dropped my flashlight. It took over two hours to get back out, and I finally reached the car around 11.”

All of that for a shot that didn’t work out.

“The sunset shot was a winner, but the second not so hot,” Dougherty reported.

Photograph by conservation photographer Jim Dougherty. All rights reserved.

If you visit the Sierra Club’s national headquarters a trio of Dougherty’s photographs face you in the lobby. Corporate art collecting continues to evolve as a business priority, and the practice recently received strong endorsements in Forbes and Seattle Business.

It’s not just in the lobby that you’ll see Dougherty’s work. Dougherty’s landscapes adorn much of the open wall space on two floors. The utility of displaying art has been confirmed by for-profit corporations including Progressive and Microsoft: it makes the spaces more welcoming to work in. Studies have shown a positive correlation between office artwork and productivity.

Co-working space COVE, which has seven locations in DC, features local art on the walls of all its locations. Adam Segal, founder of COVE, said, “Art plays such an important role in the creation of place, particularly in the look and feel of a physical space. We know art helps us create spaces where people feel welcome, productive and connected to their surroundings.”

“People want to feel loved, and when any worker sees that the company has spent some time and expense to make the workplace beautiful it helps the office culture,” Dougherty said. “When you look at these photos, your eyes have a longer focus… They help you look out into the world.”

Overall, Dougherty’s outlook is grim: “We are losing the war to defend the environment.” But he has an optimistic outlook for the future of conservation photography. “Maybe there’s so much access to these kinds of images that people develop an appreciation that there is a whole beautiful world out there,” he said. Looking at his images its impossible not to agree that there is.The well-trafficked Sierra Club offices ensure that Dougherty’s work has some consistent exposure, but he’d like to do more to distribute his photographs in the name of activism. He happily sells his work at cost with the goal of getting more eyes on nature, and more hearts dedicated to the work of nature’s preservation.

This piece was originally posted on UrbanScrawl.

No Comments