By Ilena Peng

This article was first published February 19, 2020 in The DC Line here.

Pianist Glenn Sales is experienced enough — and French composer Jules Massenet’s music is simple enough — that Sales can sneak bites of his sandwich as he plays for The Washington Ballet’s rehearsal of British choreographer Frederick Ashton’s pas de deux Méditation for Thaïs.

Sales, a veteran musician who debuted with the National Symphony Orchestra at age 14 and has played at the White House, is the music supervisor of The Washington Ballet (TWB). He plays live music for the dance company’s performances — and for classes and rehearsals at its Wisconsin Avenue NW school, filling a role that in smaller educational programs has been replaced with CDs and phones. Sales concedes that the presence of more ballet schools means more students learn the art, but he explains that widespread use of recordings favors consistency and predictability over nuanced shifts in a song’s mood or speed.

“This is why we have live everything. It never becomes routine,” Sales said. “I think that’s the death of things, when it becomes routine, an arid routine. Because then your performances can become that — just an arid routine — and I think the No. 1 sin is to bore the audience, and I think that’s what would happen.”

Sales grew up in Silver Spring, Maryland, enrolling at The Juilliard School in New York at the age of 17 on a full scholarship. After the Kirov Academy of Ballet in Northeast DC opened in 1990, Sales played at the school for a decade. More recently, he and cellist Yo-Yo Ma held music workshops in 2012 with DC elementary school students. Sales later performed at the White House in collaboration with Juilliard president and former New York City Ballet principal dancer Damian Woetzel.

The crossroads of ballet and piano isn’t well-known as a career path, with only a few programs tailored to providing pianists with the specific training needed to accompany dancers. Like many of his colleagues, Sales stumbled into the field. At Juilliard, dance teacher Hector Zaraspe knocked on Sales’ practice room door, telling him that dancers could use someone who played piano with “so much color and so much verve.” Soon after, Sales began learning more about dance and spending more time with Juilliard’s dance students.

TWB has 22 accompanists in all, and several have similar stories. Michael Parker got his start accompanying opera singers, and Kelly Lenahan flourished as a graduate student in London under the mentorship of a ballet accompanist for England’s famed Royal Opera House and the English National Ballet.

Lenahan, who joined TWB last July, says she had “no idea” until four years ago that being a ballet accompanist was a potential career path. The career had never been mentioned in her undergraduate or graduate piano studies, but then she met Nicki Williamson, a pianist who has worked with most of London’s major ballet schools. After attending Williamson’s weeklong workshop, Lenahan returned to the United States and began playing for ballet classes at a high school in Boston and for Harvard University’s student-run ballet company.

Lenahan studied and performed Irish dance for many years, and she says her background has helped her recognize just how much her musical approach and energy at the piano can affect the dancers. Lenahan recalls enthusiastic performances of live fiddle or accordion music boosting her confidence as a dancer. She describes playing for dance as a “beautiful collaborative process” easily distinguishable from the more passive dancing likely to occur when listening to a recording.

“Sometimes the dancers to me are almost like a mirror into what I’m playing,” she said. “I see the ways that they interpret things, or I see in their movements responses to the music that I didn’t necessarily hear or anticipate. So there’s always this kind of inspiration in that for me.”

For his part, Parker — who has played at TWB for 13 years — says accompaniment demands more than just the virtuosity required of a solo concert pianist. He carries a trove of music with him to classes, labeled and organized so he can work with the teacher to select and rearrange appropriate pieces.

“It’s not about the pianist capturing the spotlight,” Parker said. “It’s about the pianist in some serious way melding with the dancers or the singers.”

Parker says he sets his personal musical preferences aside and aims to play pieces he knows a teacher or dancer will like.

“The happy dancer is probably a better dancer than an unhappy dancer,” he said.

The most gratifying part of the job, Parker says, are the moments when he feels that he has contributed to the dancers’ “artistic experiments” — particularly the ballet school’s teenage students as they mature and develop their artistry. Moments like these, Parker said, bring tears to his eyes.

“The ideal is that [the music] helps the dancers do what they have been instructed to do and, in a certain sense, leads them — and, in another way, follows them,” he said.

Based on his years of experience, Parker says that dancers and singers use their bodies to express emotion in the same way musicians use their instruments to do so.

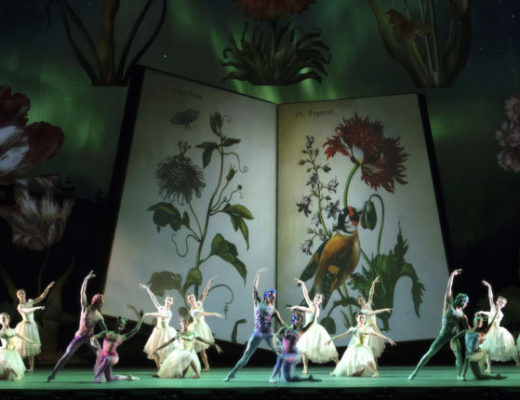

Other similarities arise as well. Just as dancers learn to pace themselves to avoid injury, Sales knows to avoid playing with his fingers splayed out whenever possible, keeping his fingers together to preserve his muscles during long six- to seven-hour workdays. The music for Méditation for Thaïs, for instance, is “relaxed” — without the “gazillions of notes” in pieces like Peter Ilyich Tchaikovsky’s Piano Concerto No. 3, which is used in choreographer and New York City Ballet founder George Balanchine’s Allegro Brillante. With pieces like Piano Concerto No. 3, Sales says he omits certain notes that make little noticeable difference to conserve energy in rehearsal. Sales played both pieces for weeks as the company rehearsed for Balanchine + Ashton, which opens Wednesday and continues with seven performances over five days.

Over the years, Sales has watched from the piano as young dancers matured, seeing some join other companies, retire or become teachers. Sales first joined TWB as a pianist in 1987, where he stayed until 1990 when he joined the newly founded Kirov Academy. After a decade at Kirov and then 15 years at Maryland’s American Dance Institute, he returned to TWB as the company’s music supervisor in 2016.

The structure of a ballet class remains the same, almost always starting with the slow warmup pliés. But the atmosphere is new each day, and Sales says the job stays fresh as he pursues a higher level of artistry.

“I’ve been blessed in that what I do does not feel like a job at all,” Sales said. “It doesn’t … feel like work for me because it’s all in pursuit of something — something much, much higher.

“I know it’s elusive,” he said. “There’s a certain truth, a certain beauty that I’m always trying to reach higher and higher to get to — but never quite getting it.”

No Comments