An incisive and visceral exploration of American race relations, policing, and the criminal justice system.

By Jordan Ealey

This article was first published January 31, 2021 in DC Metro Theater Arts here.

“It’s not what you are, it’s what you don’t become that hurts.” This quote by musician Oscar Levant is what opens the film Spook. Based on a solo stage piece by the same name, written and performed by DC theater artist Meshaun Labrone, Spook follows the final hour in the life of Darryl “Spook” Spokane, a Black former police officer. He is awaiting lethal injection for committing what is described as one of the biggest mass shootings in American history. His story has attracted significant media attention. It is in this set-up that Spook explains what was behind his violent crimes, resulting in an incisive, haunting, and visceral exploration of American race relations, policing, and the criminal justice system.

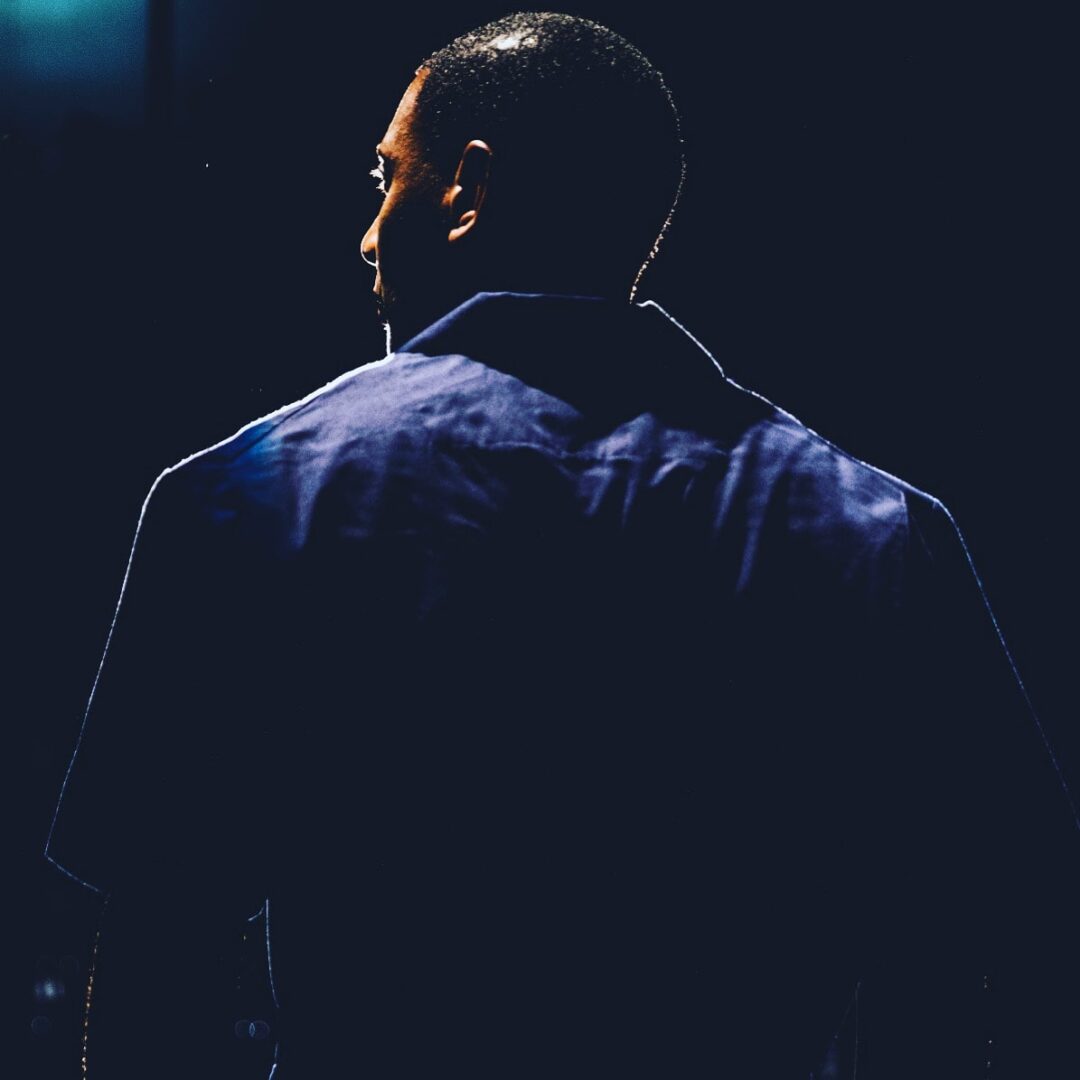

Meshaun Labrone in ‘Spook.’ Photo courtesy of Justin Featherstone.

Unlike many plays that are transformed into films, Spook (produced by Flying Scoop Productions) enhances its theatrical qualities rather than attempting to diminish or get rid of them. For instance, a common device in scriptwriting is “raising the stakes” to infuse a narrative with tension. Labrone skillfully and cleverly accomplishes this with the countdown timer, ever looming in the upper left corner of the film. We, as the audience, get to experience this man’s life slowly ticking away, literally running out of time. The narrative frame additionally includes a live televising of the lethal injection, the first one to be done in American history. Though Spook himself never touches upon this fact explicitly, one cannot help but think about what it means to see a Black man die as a part of a live broadcast, what it means for this to be the first of its kind. There were many horrific murderers in history who were still granted privacy at their deaths. Though at the film’s beginning, we learn that there is a chance for him to be granted a pardon by the Governor, it becomes clear through Spook’s story that he is not going to receive one. Spook shows no regret for the crime that he has committed; like the Levant quote that opens the film, he only mourns what he could not and did not do.

Spook’s dubious and ambiguous morality is a part of what makes the film a strong one. There are moments throughout Spook where it is both easy and difficult to “root” for him, wondering whether he is an anti-hero or a villain. The film’s darkly comic moments come unexpectedly, such as Spook’s joke about 1-800-HEP-A-NIGA, a short interlude of a “commercial” for a fictional hotline to help incarcerated Black people. Another rootable moment comes when Spook discusses his heartbreaking reason for joining the police force: to help Black people due to the injustices he both experienced and witnessed. It seems that while he does not regret the crimes he committed, he regrets that he could not be the change he wanted to see in the police force.

Certainly, moving from a stage to a screen can present problems for many productions; however, Spook skillfully navigated the adaptation. A haunting, eerie image of Spook early in the film of his darkened face gradually becoming darkened so that only his eyes remained was striking. Direction by Nate Starck leaned into the script’s dark thematic moments, retaining its theatricality in its one-room setting with focus only on the character of Spook. Labrone’s performance as Spook was captivating; though he was the sole person on screen for most of the film, he infuses the narrative with such conviction that my attention was rapt the entire time. A particularly virtuosic moment where all of the production elements coalesced beautifully was where Spook was criticizing the Black church and an organ scored his speech. The original music by Devin Spear, which could faintly be heard through the duration of the film, enhanced the dark visuals and haunting themes.

Labrone’s past as a police officer in the Washington, DC, area undoubtedly seeped into his stunning indictment of American policing. John Stoltenberg notes a similar sentiment in his 2018 review of the stage version, which debuted and ran at the Capital Fringe Festival, linking the commentary of the play to Labrone’s own lived experiences. The narrative unfolds in a way that audiences will be constantly questioning their personal biases and baggage, forced to confront realities about race in this country. But it was exactly this question of “audience” that I sat with as I viewed the film: for whom and to whom is Spook speaking?

Lawrence Glover (Prison Officer), Meshaun Labrone (Spook) and Jennifer Knight (Reporter) in ‘Spook.’ Photo courtesy of Justin Featherstone.

I could not help but cringe when the film opened and a dead Black female body covered in pools of blood flooded my screen. I viscerally reacted when Spook discussed how hard “niggas” made his job as a police officer. Yet I appreciate the ways that Spook broaches some intracommunal issues. One of Spook’s victims, a Haitian immigrant, was blatantly discriminatory toward Black Americans. Often, online spaces such as Black Twitter discuss what is referred to as the “diaspora wars,” where Black communities outside of the United States will air their grievances with the so-called monopoly on Black culture held by Black Americans. As the U.S. is a colonial force with far-reaching control of countries in the Global South, it is easy to see where the disdain comes from. My discomfort, as a Black American viewer, comes from this sentiment from Spook as an “explanation” for his crime. Though Spook is ambiguous as to whether its central character is supposed to come off as a sympathetic protagonist, I do worry about the perpetuation of certain narratives in the film.But ultimately, I found Spook, even in its violence, to be compelling, well-done, and sharp. Perhaps its strength lies in its resistance to ease and comfort, in its place critique and challenge. It was difficult for me to believe that a Black man, who grew up surrounded by the effects of anti-Blackness, would place faith in this violent and anti-Black system, but that in and of itself could be Labrone’s own critique of Black neoliberals. At the film’s conclusion, after Spook’s execution, the screen was black for a long time. I stayed there, along with the blackened screen, deep in contemplation about what I had just witnessed. Spook is a whirlwind hour of complex and uncomfortable narratives around race in America, but it will leave you plenty of time to reflect.

No Comments