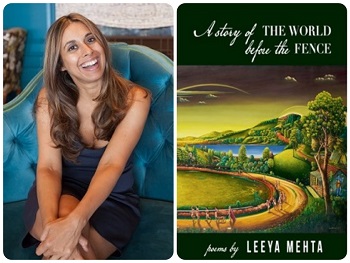

The poet/columnist talks community, multiculturalism, and feeling terribly possessive of her desk.

By Nyah Hardmon

This article was first published March 16, 2021 in Washington Independent Review of Books here.

Award-winning poet, novelist, and essayist Leeya Mehta writes because she’d “die otherwise.” In her work, Mehta — who is also a columnist for the Independent — confronts her heritage head-on, showcasing a distinct pride in where she comes from and how that upbringing affects where she is going. She does so most recently in her new poetry collection, A Story of the World Before the Fence.

In A Story of the World Before the Fence, you journey from Persia to India all the way to DC. Do you find that your work is influenced by international cultures?

Yes. I come from this community of [Zoroastrian] Persian immigrants. Most Parsis came to India over a thousand years [ago], but my father’s side is third-generation Iranian. Living in India, you’re at the crossroads of so many civilizations; you’ve had multiple colonial masters, and they’re integrated into our culture. So growing up there and coming to America in my twenties, having gone to England for my education and living in Japan and then spending the better part of the 2000s in Washington, which is a big international city, there is no one home, but then at the same time, we have to create the sense of home.

In this collection, you discuss that sense of unbelonging, but then you use relatability to make audiences feel like they do belong right here in the text. Talk to me about that paradox.

For many, there’s this sense of “Where is home?” I remember growing up with a family that I was very close to, and the man was the first chief of police for India after Independence. He was posted everywhere around India, and my grandfather, who was his friend, was posted everywhere. They were all “company men,” or people who were always moving, and there was a sense of “Where is home?” Home is where you were born, to some degree, but at the end of the day, human beings have always migrated. I’ve come to embrace the reality this family shared, that “Home is where I am.” A lot of my poetry is rejecting that idea of belonging that’s nihilistic [in favor of] a belonging that’s more inspirational. The idea of sanctuary, of potential.

Because your writing takes readers on transcontinental journeys, do you find any trouble in embracing your own culture without being boxed into the “international” genre?

I haven’t so far. Having multiple identities is so useful since I come from such a small community. I’m culturally from a community of 80,000 people, and so it’s like a little tribe. There’s so much specific humor and culture that I think people are drawn to. I don’t find it very limiting given I write fiction, short stories, poetry, and I do a column [for the Independent] called “The Company We Keep.” I have this really great opportunity to explore a variety of places and people. It’s really very liberating.

You dive heavily into ancestral trauma and how it travels to future generations.

My poetry tends to refer back to historical events a great deal, but my fiction is where I really carry the intergenerational trauma. My novel Extinction is about four generations of women from India who pass this intergenerational trauma to each other. The idea of Extinction is how do we stop it, how do we end it, how do we get past it, and that’s what the title signifies.

I notice you play with different styles, jumping from this somber, serious tone to lighthearted humor. Do you mix elements of different genres into your work?

Thank you for saying that. I love it when someone says they notice some lightheartedness or humor. I was actually deliberating how to be both somber and humorous at the same time. My genres tend to be quite separate from each other. The fiction is very different from the poetry. The only time that they do tend to overlap is when I write certain poems where the prose and the poetry work really well.

Talk to me more about your creative process.

I have a playlist for each book, and sometimes I’ll listen to one when I’m doing another. I don’t have a space of my own, really, except my desk. So I’m terribly possessive of my desk. Ideally, I work six hours a day. I have specific music. I tend to only read for my book, and I read for my column. It’s very difficult for me to add in other reading because to stay pure to the voice of the novel — in different directions, especially when you’re writing a novel over 10 years — it’s difficult to step out of it and go off.

Has your writing been affected by the pandemic?

Definitely. Very much affected. The nice thing is that I’m enjoying doing more podcast-style interviews on Zoom of other writers. Especially before the 2020 election, there was this sense that we had a community depression from the last four years, and then [again] with covid, and I suffered from all of that just as much as everyone else. It deeply impacted my ability to write. At the same time, I have been writing 80,000 words of a new novel, so I’m sure that I’m actually writing but I don’t feel like I’m writing. There’s this sense of disconnect with the outside world, but I am very grateful to have writing as my profession right now. I feel like it’s a big blessing.

Besides Extinction, do you have any other projects on the horizon?

I’m focusing all my attention on Extinction because I’m trying to get it ready to send out to publishers this year. And then the next novel is a romance novel that’s set [against] the backdrop of a very big riot. So those are the big projects, but I have so many projects. The next three years are going to be very exciting.

No Comments