This article was first published in The DC Line here. It was developed within Day Eight’s week-long, 2021 summer arts journalism institute.

With just the movement of a computer mouse, a silver pitcher covered with two winged camels and foliate patterns is viewable from all angles and at various scales. This Central Asian artifact, made in the late seventh or early eighth century A.D., is just one of numerous 3D items that visitors can access through a National Museum of Asian Art virtual exhibition. The museum, part of the Smithsonian Institution, is far from alone in having launched virtual exhibits at a time when the pandemic kept museums and galleries from fully reopening.

Even as DC art institutions like the National Museum of African Art and the Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Gallery have gradually reopened their doors to the public, not everyone is ready to head downtown, particularly with the rise in COVID-19 cases due to the spread of the delta variant. Luckily, the city’s museums have adapted over the past year to offer an equally valuable experience through online exhibitions. Antonietta Catanzariti, assistant curator for the ancient Near East at the National Museum of Asian Art, notes that visitation to their website has doubled in the past year, and remains high even as the museum and others have reopened.

That’s hardly surprising. “Virtual exhibitions are similar to physical exhibitions, often capitalizing on the web’s capacity for a personalized experience in which the user directs their own journey,” wrote Ngaire Blankenberg in her 2014 book Manual of Museum Exhibitions. (Blankenberg, formerly a cultural consultant, became director of the Smithsonian’s National Museum of African Art in July.)

Here are examples of what you can find online from three DC museums:

National Museum of Asian Art (formerly the Freer Gallery of Art and Arthur M. Sackler Gallery)

The Sogdians: Influencers on the Silk Roads, curated by the National Museum of Asian Art, has been open since 2019. With no specified end date, this timeframe is rare for physical exhibitions, which are usually open for weeks or months.

Kimon Keramidas, New York University professor of digital humanities and a curator of the show, said digital exhibitions can usually last for five to six years before advances in technology lead to complications. Even then, however, they can still be updated and recovered.

Digital exhibitions also allow for the display of artifacts that might not otherwise have been available. The curators of the Sogdians exhibition, for instance, decided to go digital due to challenging geopolitical circumstances, according to Keramidas: The trade embargoes that followed Russia’s invasion of Crimea in 2014 prevented important collections from loaning objects.

The exhibition is packed with about 700 pieces of material, including 3D models, images, custom maps, drone footage and more. The exhibit’s subject matter is similarly rich in diversity.

Julian Raby, director emeritus of the museum, calls the Sogdians an “underestimated” people. They were an ethnic group that lived in the first millennium A.D., occupying a vast terrain of Eurasia and significantly shaping Silk Roads culture and commerce. As merchants, craftsmen and entertainers, the Sogdians lived and traveled everywhere from China to the lands of the Byzantine Empire.

In one section of the virtual exhibition, the visitor follows a historical trade route and sees a moving map, photographs of the terrain, and text describing each location. Unlike maps on gallery walls that could be easily overlooked, here the geographic tour takes center stage in the experience.

“There is a sense of immediate rapport that could be quite powerful,” Raby said in an interview.

Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Gallery

Hirshhorn Museum’s Lost in Place: Voyages in Video debuted in May 2021 as a direct response to the pandemic, which the exhibition text states had “greatly diminished our radius of movement — collapsing home, office, and school into a single location — and recalibrated our sense of personal boundaries.” Drawn from the Hirshhorn’s permanent collection, the digital exhibition brought together 11 videos by contemporary artists from around the world. They were each made available for viewing in sequential and overlapping four-week spans, with the last one accessible through Aug. 20.

One of the videos, Laure Prouvost’s Swallow, inundates the viewer’s eyes and ears with a sensual intimacy that is almost unsettling. While following a group of nude bathers in a stream, Prouvost’s camera fades in and out of extreme close-ups on body parts, flapping fish, and crushed berries. This all occurs while recurrent sounds of breathing and shots of an open mouth span the entirety of the video’s run. After a year of Zoom-room socializations, such sudden closeness with bodies and nature is especially striking.

Purchase Fund, 2008 (Photo courtesy of Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden)

Among the other featured videos were Pierre Huyghe’s One Million Kingdoms, starring a digital avatar traversing a lunar landscape generated by her voice; the artist collective Superflex’s Flooded McDonald’s, a meditation on the fast-food restaurant chain’s material footprint that depicts a kitchen slowly filled with 20,000 gallons of water; Carlos Amorales’ Dark Mirror, featuring animations of wolves, bears, falling airplanes, and other images evocative of danger; and Guido van der Werve’s Nummer Negen (#9): The Day I Didn’t Turn with the World, a time lapse of the geographic North Pole, where the artist stood for 24 hours facing away from the sun.

National Museum of Women in the Arts (NMWA)

The NMWA’s online exhibitions, which are running indefinitely, mimic carefully crafted walking tours. They employ sequences of web pages that are as immersive as museum displays, which viewers navigate with their mouse and arrow keys.

The first online exhibition curated by the museum is the ongoing show A Global Icon: Mary in Context, which launched in 2015. The featured sculptures and paintings of the Virgin Mary come from Europe as well as Japan, Ethiopia, Mexico and more. With each page turn, the web window can zoom into a detail of the work or present an explanatory video that highlights the various contexts in which the biblical figure Mary appears.

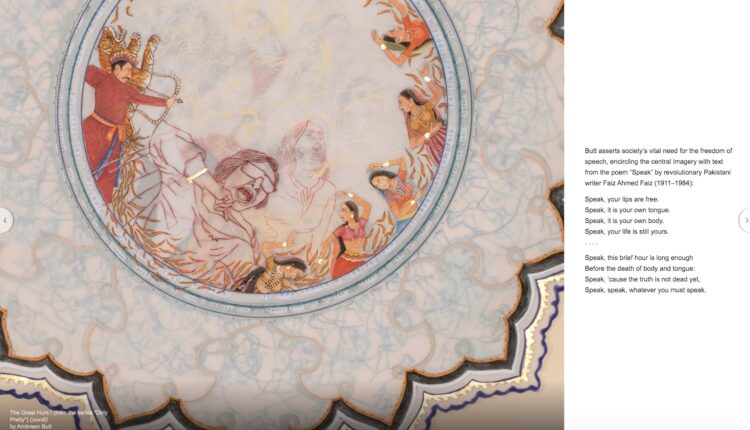

The same kind of seamless passage from content to content characterizes NMWA’s newer exhibitions, like Ambreen Butt — Mark My Words, which launched last year and interlaces videos of her work process with displays of her paintings, prints and collages.

In June 2020, the museum redesigned its website to host its online exhibitions as part of an ongoing effort to enhance its digital platform. Laura Hoffman, the director of digital engagement, explained that the pandemic had prompted discussions in the field about what a museum experience without physical access ought to look like.

With NMWA undergoing a major two-year renovation as of Aug. 9, Hoffman said the pandemic provided a useful — and timely — opportunity to explore the museum’s digital capabilities leading up to its temporary closure.

“The pandemic almost felt like a test run for all the digital possibilities there are,” Hoffman said.

Roy Gao was born in Boston, MA, but grew up in Pittsburgh, PA and in Beijing, China. Before college, he lived in and studied in both the United States and China. Roy received his bachelor’s degree in 2021, from the University of Pittsburgh, with a double major in Art History and Philosophy. For the fall, he has been admitted to the Master’s program in Modern and Contemporary Art History at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago. In 2020, Roy was a top-ranked applicant for the Fine Foundation Fellowship at the Carnegie Museum of Art (before the fellowship was cancelled due to COVID-19). He was the curator of “Footsteps” at the China Millennium Monument in 2019, and co-curator of “This Is Not Ideal: Gender Myths and Their Transformation” held at the University Art Gallery of the University of Pittsburgh in 2018.

No Comments