By Teniola Ayoola

This article was originally published in Washington City Paper here.

On the Fourth of July, Beyoncé Giselle Knowles-Carter stood center stage at Northwest Stadium in Landover and redefined what American music, legacy, and spectacle looks like. Her Cowboy Carter Tour stop wasn’t just a concert—it was a living, breathing art installation, a cultural exegesis, a Black feminist thesis, a family archive, and a stage production worthy of Broadway.

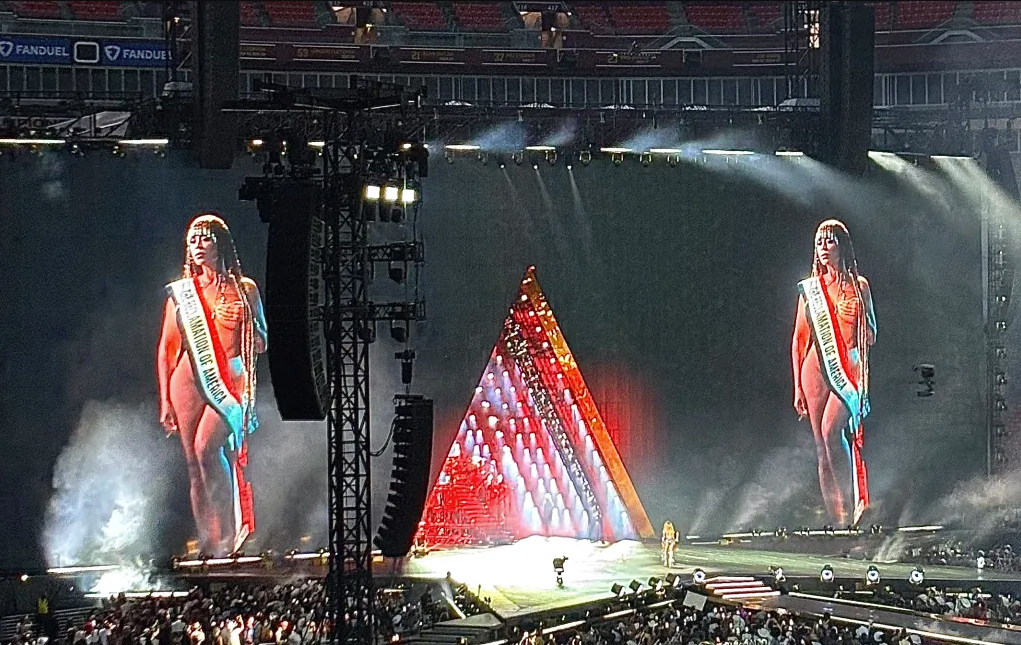

In one of the night’s most visually arresting moments, Beyoncé appeared on screen as a larger-than-life figure, strutting through major cities across the U.S.—from Houston to New York to Las Vegas. But when she arrived in D.C., gliding past the White House, towering over the Washington Monument and Lincoln Memorial, the stadium erupted.

There is no place more loaded with meaning on July 4 than D.C. For Beyoncé to perform this show—one rooted in Southern Black identity, defiance, and American reclamation—on this date felt like a deliberate choice. The show opened with a knowing wink: Beyoncé at the center of a screen flashing red, white, and blue, performing “The Star-Spangled Banner.” Her version, however, was laced with the rebellious instrumental arrangement originally performed by Jimi Hendrix at Woodstock in 1969.

Despite Cowboy Carter’s musical brilliance, some critics and country purists questioned whether Beyoncé belonged in the genre at all—a familiar refrain for Black artists in traditionally White spaces. The song “Texas Hold ’Em” was initially rejected by some country radio stations, reigniting long-standing tensions about gatekeeping in American music. After rejecting a listener’s request for “Texas Hold ’Em,” the manager at Oklahoma radio station KYKC, explained, “We do not play Beyoncé on KYKC as we are a country music station.”

Beyoncé addressed the criticism head-on. The backlash didn’t undermine her message—it amplified it. From the moment fans trickled into the stadium—many clad in denim, fringe, rhinestones, boots, and custom cowboy hats—it was clear this wasn’t just a tour; it was a movement. And when the singer finally emerged, cloaked in a massive American flag robe, Beyoncé made it known: This wasn’t about performing for a nation. This was about reclaiming it.

Backed by pounding drums and glittering visuals, Beyoncé asked the 50,000 or so audience members, “Can you hear me? Do you feel me?” The audience responded loudly. What followed was a dynamic set list that unfolded over roughly two hours. There were songs from Cowboy Carter, but also from 2003’s Dangerously in Love, 2008’s I Am… Sasha Fierce, 2011’s 4, and more. As strangers in the crowd belted out, “To the left, to the left…” in unison, it felt like more than a duet—it felt like community.

Midway through the concert, Beyoncé mused, “Genre is such a weird concept.” In that moment—surrounded by country riffs, rock undertones, voguing interludes, ballet pirouettes, trap beats, tap dancing, the iconic bounce-on-that-shit Riverdance step, and a drop into the gritty “Nigga ask about me” from Crazy in Love (Homecoming Live)—her point landed. She moved from elegant to guttural, soft to sharp, as if to ask: Who said I had to choose?

And in D.C., where musical legacies run deep, Beyoncé’s refusal to be boxed in echoed one of the city’s most defining genres: go-go. Born in the District and pioneered by the legendary Chuck Brown, go-go has never been just one thing. It fuses funk, soul, gospel, and call-and-response rhythms, drawing energy from both pop and percussion-heavy West African traditions.

Back onstage in Landover, Beyoncé honored her lineage. A graphic featured Black icons like Tina Turner. And at the start of “Formation,” her dancers broke into a clean, syncopated hat routine—gyrations and hip thrusts delivered with precision—a quiet, but unmistakable homage to Michael Jackson.

Outside the spectacle, the show struck deeply personal chords for the audience. For many, it was a night of full-bodied joy—dancing in the stands, sipping drinks on the party bus, and bonding with strangers over shared lyrics. Singing “Irreplaceable” together wasn’t just serendipity. It was the communal spirit Beyoncé cultivates—on and off stage.

Through it all, Beyoncé didn’t just perform. She reminded the crowd that she—and Black people, especially Black women—are America. Not in the political sense, as in presidents or lawmakers, but in the mythic one: the soul, rhythm, and story of the nation itself. Her journey from Houston girl group prodigy to global powerhouse is a story of grit, grace, and genre defiance—but also a reflection of Black resilience, ingenuity, and creative power. On July 4 in D.C., Beyoncé didn’t just put on a show—she claimed space. It wasn’t about fitting in. It was about standing firm.