by Jason Williams

This article was first published in The Northwest Current.

Witnessing the meteoric rise of Ta-Nehisi Coates from a relatively unknown journeyman journalist to a multiple New York Times list best selling author, the easier narrative to follow was Coates.

It did not matter that Coates eschewed the spotlight at first, then tried his best to redirect his newfound celebrity to the issues and the people that needed the attention. There was a segment of his readership that wanted from Coates what we typically request from all brave, new, voices that challenge the status quo – more.

With the presentation of his “Between the World and Me,” adapted for the stage by Lauren A. Whitehead under the direction of Kamilah Forbes and scored by Jason Moran, the places, people and experiences Coates so incredibly illuminates through this work are drawn to the forefront again.

The audience filed into the Eisenhower Theater at the John F. Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts to a musical mix of Stevie Wonder and Nina Simone among others. Promptly at 2:15 p.m. the music was lowered, as were the house lights. The dark curtains were pulled back and the stage revealed.

In the foreground were three clear podiums, stage right, with nine chairs and accompanying music stands. Behind them stood a tall, rectangular media screen. On top of the screen sat Jason Moran at his piano, as he was joined by Mimi Jones on bass guitar and Nate Smith on drums. The trio played softly as the cast entered on both sides of the stage.

Behind the band was a similar media scene that was synced with a larger one under it. The first image shown was cracked pavement similar to the one displayed on Coates’ 2008 debut novel, “A Beautiful Struggle.” As the actors found their seats, the music came to close when Joe Morton came out to open the production.

The book version of “Between the World and Me” is a tightly-written 152 pages without a table of contents. At its heart, the book is a letter to Coates’ then-teenage son, Samori. The power of the story is how Coates expresses his understanding of how his physical body, like the one of his son and all people of African decent, fit in the larger context of American history.

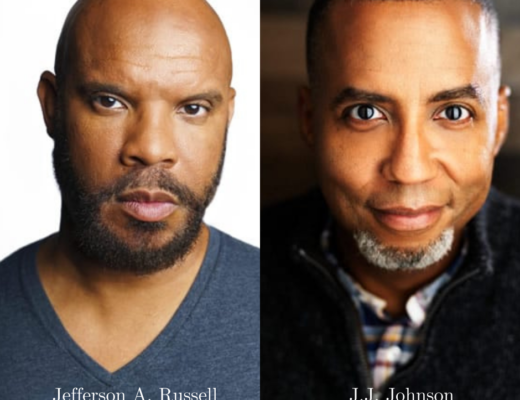

Morton opens as the book does, with setting primes for this discussion. It was a response to an interviewer’s question about what it meant to lose his body. What is clear from the outset is the pairing of the actors with the parts of the text they presented was intentional, not just for tone and annunciation, but for the history each actor brought to this work.

For example, Tariq Trotter, who is professionally know as Black Thought of The Roots, was called upon to express the difficulty of navigating urban America, being it the Baltimore of Coates’ youth or his first venture into Brooklyn after college. Trotter, only four years older than Coates, has often written about the difficulties he faced growing up in Philadelphia.

The production began to pick up steam as it entered what would be the second part of the book. At this phase, Coates is questioning, discovering and re-questioning the vast amount of history he is consuming during his studies at Howard University. This is also the time when Coates is laying claim to one of his first heroes, Malcolm X. In a beautiful convalescing of words, music, lighting and the media screens, Greg Reid and Michelle Wilson duel in rhythm and tell how Coates came to appreciate and adore Malcolm X. As they tell the story, the jazz trio played forcefully in the background. As two spotlights beamed down on Reid and Wilson, the iconic photo taken by Don Hogan Charles of Malcolm X with a rifle in his hand came into focus on the lower screen, while a picture of him smiling appeared on the upper screen.

Next, Susan Kelechi Watson, who is an alumna of Howard University, told of the cultural education Coates received at The Mecca. Dressed in black, Watson expressed with incredible joy and energy what Coates saw, heard and felt while walking the yard of D.C.’s oldest Historically Black College. There was moment when Watson beat on the podium, recreating the beat of hip-hop cyphers that happened on campus. It is then you realize that despite the seriousness of what Coates is expressing to his son and to us, this is not a tale of sorrow or fear, but rather a complicated reconciliation of the reality of being black in the country.

The moments when the actors read as an assemble where carefully used and punctuated important passages. Marc Bamuthi Joseph channeled the anger and pain of Coates as he tried to make sense of an officer-related killing of his dear friend Prince Jones. Balanced against that rage was Dr. Mable Jones, Prince’s mother voiced by Pauletta Washington. As Washington and Reid recreated this heartbreaking conversation, the audience was forced to understand why this entire venture had to happen. If not for anything else but to acknowledge the countless Prince Joneses this country creates and the mothers who are left behind.

As the performance came to an end, Morton returned to close the circle he had started with words of wisdom for Samori. They were neither overtly hopeful nor dismal, for the times we live in are far too nuance for extremes.

As Morton ended, the rest of the cast joined him at the front of the stage to a loud wave of applause. After a quick turn to thank Moran, Jones and Smith, the cast exited.

Then, a scroll of names of people lost to state-sanctioned violence rolled across both screens. The applause turned to silence while some in the audience recorded on their phones. Virtually no one left his or her seat until the last name left the screen – that of Saheed Vassell.

No Comments