Artistic Director Raymond O. Caldwell and Playwright Khadijah Z. Ali-Coleman share insider insights on the company’s exemplary community engagement.

By Jordan Ealey

This article was first published May 24, 2021 in DC Metro Theater Arts here.

Transition as a noun means “the process or period of changing from one state to another.” As a verb it means “to undergo or cause to undergo a process or period of transition.” Both definitions, from the Oxford Dictionary, point to transition as a site of possibility—defined by its errant and unfinished nature but moving toward something, whether positive or negative.

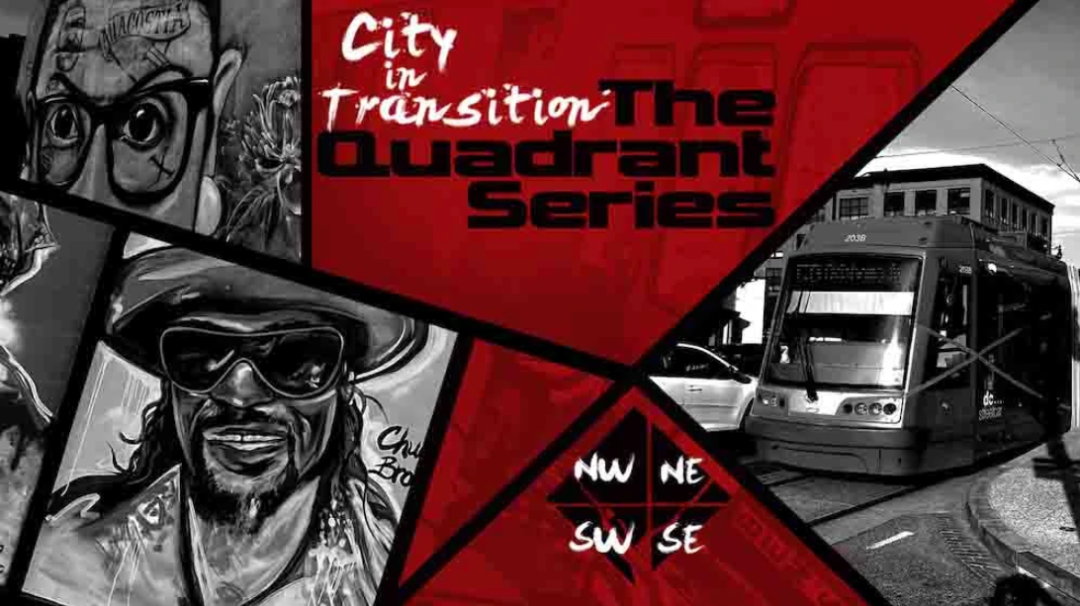

This feeling is captured in Theater Alliance’s City in Transition: The Quadrant Series, a group of pieces that explore Washington, DC’s four quadrants — Northwest, Northeast, Southwest, and Southeast — in order to stage the disparate and interconnected histories and ongoing stories of Black life in the District. Playwrights Khadijah Z. Ali-Coleman, Avery Collins, Shalom Omo-Osagie, and Leslie Scott-Jones were commissioned to represent one quadrant of the DC area and generated four stories as diverse as the region itself.

Child’s Place by Shalom Omo-Osagie, representing the Northwest quadrant, and tells the story of an intergenerational dilemma: a Black family quarreling over whether to transform its long-standing restaurant into a lounge. Besides conflict across generations, the play wrestles with gentrification and class politics. Avery Collins’s Big Fish, speaking to the Southwest quadrant, follows the journey of rapper Wizard Kelly and his untimely death. Incorporating music, the piece uses the tradition of hip hop theater. The Northeast quadrant play, Thirty-Seven by Leslie Scott-Jones, delves into interracial politics as it details the fraught relationship between a Black DC resident and a white census worker. The Southeast quadrant play, Khadijah Ali-Coleman’s Fundable, tells the story of a game show (which I’ll discuss later). Each play speaks to the others while diverging creatively to present a portrait of contemporary Black DC life.

Like Theater Alliance’s previous virtual production A Protest in 8, City in Transition employs film in creative ways. But rather than presenting a linear composition like its predecessor, City in Transition fragments the narratives and sutures scenes together out of order. What this creates is an abstract, experimental cinematic and theatrical style. I was fascinated by this generative blending of content and form. It forces the viewer to really pay attention to follow where each piece leads.

As a company Theater Alliance continues to be a leader in community-engaged work — tuned in to not only the artistic desires of leadership and staff but also a complex understanding of the inclusion of the surrounding neighborhood. This can be seen in initiatives such as Radical Neighboring — a group of tickets set aside for residents of Southeast DC, a program dating back to the previous artistic director, Colin Hovde — and has continued with recent productions such as A Protest in 8, the company’s fall digital collection, which featured the original plays and nonprofit activist organizations of the playwrights’ choices. In a social and political climate heavily attuned to issues around equity and justice, Theater Alliance seems to be doing what they have always done: modeling the convergence of community engagement and artistic practice.

But something else has been intriguing to me with the work being done at Theater Alliance, especially by its artistic director, Raymond O. Caldwell. I find, as a Black theater artist, that Black theater — and Black art at large — is often discussed for its activist or political merit and not also for what it contributes artistically and creatively. I am annoyed when critics simply write about how “important” Black art is rather than also illuminating its innovations in style or form. It’s something I always look for when I watch any work of theater but especially productions with a Black creative team. Not to devalue the political contributions that are being made, but I want to honor the artistry involved.

Due to the stalling of in-person performances because of the pandemic, Theater Alliance, like theaters across the nation, turned to digital platforms to produce. While many people have questioned what this digital turn has done to the fundamental agreement of what theater is (a live form of performance that is based on a bodily exchange among both performers and audiences), Caldwell has instead embraced the affordances of the virtual landscape. This question — “What is theater?” — remained central to Caldwell’s artistic considerations with the creative team as they were putting together City in Transition, he told me; he was not interested in simply making a film. Caldwell defines theater as “seers and doers,” as he believes “theater happens everywhere.” One of his favorite pastimes is sitting in a coffee shop and observing all the theater occurring around him. He doesn’t discount what makes theater special — its liveness — but “we have to be together for that to happen.”

This relational component is at the center of Theater Alliance’s ethos of producing artistically challenging yet communally engaging work as Caldwell realized that connecting with other people and bodies in a shared space is crucial to theater. But there is a unique component to Caldwell’s artistic and directorial style, a creative signature that I recognize: His work often incorporates play and games, specifically the device of the game show. It’s clear from both the fall 2019 Day of Absence and the more recent A Protest in 8 that Caldwell is interested in what games do and can do for intense political conversations.

“I love games,” Caldwell told me; “I think gameplay draws out some of the ugliest in us in really evocative ways.” Admitting to being a competitive person himself, Caldwell noted that people often return to a sense of play because it’s “the first way we experienced the world.” In City in Transition, Khadijah Ali-Coleman’s Fundable, representing the Southeast quadrant, harnessed the narrative and aesthetic device of a game show whose winner gets funding for their nonprofit of choice. This not only presented ample opportunity for socially relevant commentary on gentrification and the toxic nonprofit world but also gave Ali-Coleman space to explore her humorous side.

Fundable originally had an entirely different tone, plot, and characters, Ali-Coleman told me. As the process of creating City in Transition was underway, Caldwell encouraged her to focus her play more. Retaining the character of Natasha and her desire to open a nonprofit, Ali-Coleman also told me that her tonal transition to Fundable was partly inspired by seeing Day of Absence at Theater Alliance. The theme of “games” was important to exploring the nonprofit industry because, as Ali-Coleman detailed, “it’s all a game.” As is displayed in the play — which features two Black contestants, a white contestant, and a Black host — it is revealed that the game show was rigged from the beginning. Referring to her experience working in DC’s nonprofit sector, Ali-Coleman remarked on how she observed what got funded, who got funded, and why they got funded: it was all a game.

Confessing to being “very serious,” Ali-Coleman nonetheless welcomed the challenge to incorporate comedy into her work. “I think I’m funny, but if my purpose is to really say something, then I’m starting to realize that the comedy aspect makes it more digestible.” While she also went on to add that she found it sad that it takes shrouding something in a humorous tone for it to be legible to audiences, I was fascinated by her observation. Humor and comedy are certainly bridge-building tools for conscious coalition and solidarity, but they can also be a double-edged sword based on who is laughing and why.

Returning to the idea of transition was important in my conversations with both Caldwell and Ali-Coleman. Transition struck me as a peculiar word because it could be considered neutral and apolitical, as opposed to maybe City Gentrified or City Stolen, which all the pieces imply the project could have been called. So why transition? I asked them both what transition meant to them, especially in the context of City in Transition and DC writ large.

Ali-Coleman — DC-born and -bred (like many of the quadrant playwrights) — told me that many of the communities, organizations, and even people who were around in the early 2000s are no longer there. This has affected DC’s political structure, as observed by Ali-Coleman, where even local governments and local activism have been transformed due to the transition. Ali-Coleman, however, does see DC’s youth being more active than ever, with campaigns such as #DontMuteDC — which protests white gentrifiers complaining about the consistent playing of gogo music — attempting to preserve what is left of DC’s Black social structure.

But Ali-Coleman also made a poignant observation about transition — its meaning as signifying death, the ultimate transition. “What’s left if there is no community to come back to? To give back to?” she questioned. Our interview also revealed the depth of Ali-Coleman’s personal ties to her hometown of DC and the pain that gentrification has intimately caused her. Being from Atlanta and seeing a similar thing beginning to happen there as has occurred in DC, I see that gentrification is no laughing matter. It makes Ali-Coleman’s ability to tell that story through humor, irony, and pastiche even more resonant.

Like me, Caldwell is a DC transplant from the South and, similar to me, he also heard stories prior to moving here of the famed “Chocolate City” — where Black people were said to be living and thriving unlike anywhere else in the world. However, when he arrived here thirteen years ago, “Chocolate City” was nowhere to be found. After reading Chris Myers Asch and George Derek Musgrove’s Chocolate City: A History of Race and Democracy in the Nation’s Capital at the top of the pandemic, Caldwell said he was led down a path of DC history.

“Black folks have been able to create community here in really dynamic and drastic ways. And that idea of community is constantly in transition,” Caldwell noted. Washington, DC’s Black history is truly rich — given how this city was a place of mobility for Black people, inasmuch as it was a place of subjugation. Caldwell is interested in (and simultaneously concerned about) “the aesthetics of Blackness” that is “on the rise” in DC, communicated visually and artistically through things such as murals and programmed Black artists. But rather than ending a conversation by claiming something like “gentrification” in the title, Caldwell recognized that Theater Alliance’s goal has always been to start conversation.

Ultimately, I find Caldwell’s, Ali-Coleman’s, and the creative team’s artistry to be inspired. Their Quadrant Series sparked what can be considered a love letter to Washington, DC, a city ever in transition.

No Comments