By Whit Davis

This article was originally published in The DC Line here.

The High Ground, a new play by Nathan Alan Davis, poses a fundamental question: “What is a love story?”

In attempting to answer, Davis manipulates time and loss to deliver a metaphoric “love” story centered around the Tulsa Race Massacre, in which an estimated 300 Black people were murdered and approximately 10,000 more rendered homeless in 1921. Davis’ tale serves as a vehicle for commentary on the relationship Black people have to the past, present and future.

The High Ground makes its world premiere at Arena Stage through April 2 and is directed by Megan Sandberg-Zakian, who previously worked with Davis on Nat Turner in Jerusalem. The connection between director and writer is immediately recognizable in The High Ground. The play’s lively, bold and almost spectacle-like structure affirms that when a director and playwright are in tandem, it is felt through the engagement from the audience.

This story has all the ingredients for a spectacular tale: history, love, metaphors, humor and dramatics. Yet it was the subtext related to the Black woman character(s) that stayed with me long after the play ended. The love story — or the attempts by Davis and Sandberg-Zakian to communicate that The High Ground is a metaphor-laden love story — comes with rewards as well as costs.

Phillip James Brannon delivers a dynamic performance as Soldier, displaying every quirk and idiosyncrasy you would expect of someone who has survived a violently traumatic event and may be suffering from PTSD. Soldier struggles with remembering and moving forward as he builds his whole life around the tower on Standpipe Hill — a vantage marked for its role in the violence against Black bodies — as those in the present move through the world untouched by what happened to the Black people of the Greenwood district in 1921. Soldier represents the past that Black people wrestle with and carry with them in an Anti-Black world, yet he searches and waits for his “wife,” present and future.

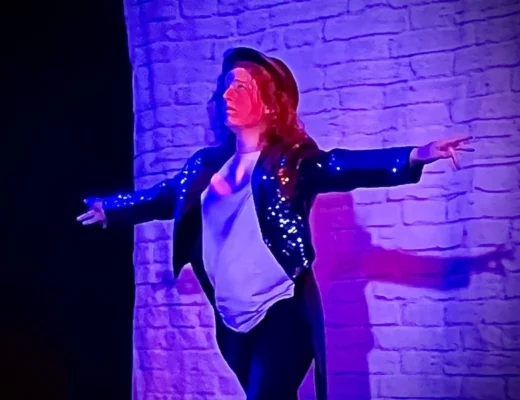

Nehassaiu deGannes, as Victoria/Vicky/Vee/The Woman in Black, has a slow buildup in her performance but finds her groove at about the third scene and in her third costume. The costume changes, designed by Sarita Fellows, are as significant as the changing of her character’s name, and with each new scene she attempts to make Soldier “surrender” to her, as she portrays the present and future for Black people. She is supposed to be the way forward.

Outwardly, the interpersonal dynamic seems like that of a woman trying to help Soldier. But the character’s transitions — from a graduate student studying public health at Oklahoma State University, to a police officer without a service weapon, to cosplaying with Soldier or even traveling back in time to a memory that they both share — raise many questions about the cost of imagination. Why did Davis make these choices? Why choose to have this character be a police officer without a service weapon? The relationship between Black people and police is sensitive, and evoking it here seems to be a careless choice that helps create an indecipherable message.

This part of the play becomes disjointed, which leads to a larger question: Why place upon a Black woman the burden of convincing a Black man tormented by the past to “surrender” to the present and future? Victoria/Vee/Vicky makes multiple desperate attempts to help Soldier leave his post at the tower on Standpipe Hill. This creative choice brought to my mind Zora Neale Hurston’s Their Eyes Were Watching God and Black women being the mules of the world. Davis leans so far into the trope of “the strong Black woman” that it causes me to wonder if he can reckon with a past, present and future that acknowledges the history of the subjugation of Black women. The Tulsa Race Massacre is a shared history of all Black people. The burden of slavery is another shared experience that still is very present, and no mythical Black woman, even under the guise of a metaphoric love story, can save us as a people.

The High Ground, on one level at least, is a metaphor that asks us to think about the Tulsa Race Massacre and the killing of Black bodies. Still, I want the audience to dig deeper into how even the imagination can become a place of violence against Black bodies, especially Black women and Black queer people. As Davis attempts to drive home the theme of “surrendering,” I walked away thinking about the sacrifices we demand of Black women.

I’m still no closer than when I started to understanding “What is a love story?”

This article was produced in conjunction with Day Eight’s February 2023 conference on “Rethinking Theater Criticism.” The DC Line worked with conference organizers on the New Theater Reviewer project, an initiative to grow the cohort of qualified local reviewers. Whit Davis is one of several writers assigned as part of the conference to write a review for The DC Line,DC Theater Arts orDC TRENDING.

No Comments