by Haley Huchler

This article was originally published in Washington Independent Review of Books, here.

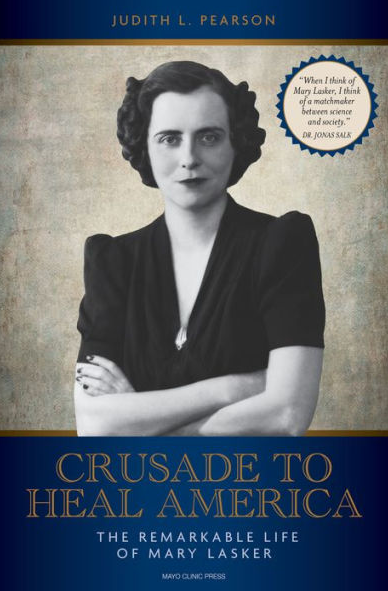

“Mary Lasker had never looked through a microscope, performed surgery, or spoken from the floor of the Capitol,” writes Judith L. Pearson. “She simply had an unbridled belief in possibility.” Crusade to Heal America: The Remarkable Life of Mary Lasker Pearson illuminates the accomplishments of her subject, a woman who arguably did more than any other individual to improve the health of Americans throughout the 20th century. The main source material for the book is an oral history Lasker gave to Columbia University in 1962, recording it on the condition that it not be made public until after her death. Pearson uses Lasker’s words to great effect in this artfully crafted biography.

The daughter of an Irish immigrant and a Midwestern banker, Mary Woodard grew up in Watertown, Wisconsin. While a student at the University of Wisconsin-Madison, she fell ill with the Spanish flu, one in a long line of childhood illnesses she endured. These early experiences with sickness fueled her lifelong interest in medical research.

After recovering, Mary headed east to pursue her passion for art at Radcliffe College, the only school then offering a major in art history. She soon wound up working at a gallery in New York City. It was there she met her first husband, and together they enjoyed a lavish life of art collecting and international travel until the stock-market crash of 1929 destroyed everything, including their relationship. It was her second marriage, to Albert Lasker, that would spark her crusade into public health. (Although Mary is the heroine of this story, Albert was a devoted and passionate partner in her efforts. His death from colon cancer in 1952 only heightened her dedication to the cause.)

The Laskers were a well-connected pair. Albert, from his sickbed, received hand-painted get-well cards from Henri Matisse and Salvador Dali; Mary attended balls with Britain’s royal family and Winston Churchill on the eve of the Second World War. With their money and connections, they held the world in the palm of their hands. But what they most wanted to do with their considerable resources was improve the health and longevity of fellow Americans.

The couple’s interest in campaigning for a cause formed early in their marriage. The Laskers spent their honeymoon at the Democratic and Republican national conventions, and they later became involved in supporting the Birth Control Federation of America (it was Albert who suggested it be renamed Planned Parenthood). In December 1942, the pair founded the Albert and Mary Lasker Foundation to promote better health through education and research. A decade later, after Albert’s death, Mary persisted in the effort, rallying for more dollars to be spent on heart disease and cancer research each year.

Pearson’s clear and concise writing serves the narrative well. Her attention to detail is stunning, with reconstructed conversations so intimate, you might wonder if she was a fly on the wall at Mary’s meetings with President Eisenhower or lunches with Lady Bird Johnson. While the second half of the book gets mildly bogged down with the minutiae surrounding various bills and partisan debates, it does offer important insight into the difficulties of making large, meaningful changes via public policy. Despite working toward a goal almost everyone supported — fewer deaths from disease — Mary faced immense challenges as she proceeded through the ungreased gears of Congress.

There’s no single resounding moment in the story when she finally achieves all she ever dreamed of. Rather, there’s an accumulation of tiny shifts — which she helped create — that spurred real change. Today, Americans are much more likely to recover from major illnesses like cancer and heart disease than they were 70 years ago. After reading this eye-opening account of Mary Lasker’s life, you’ll know whom they should thank.

No Comments