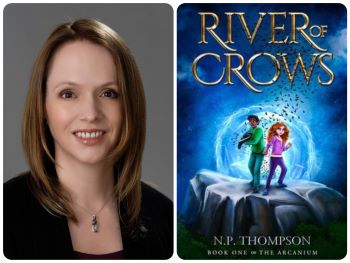

By Imani Nyame

This article was originally published in the Washington Independent Review of Books here.

In her debut novel, River of Crows, the first installment in the Arcanium series, Canadian author N.P. Thompson takes readers into the magical and dangerous world of Arcania, where 12-year-old Ty Baxter forges life-changing friendships as he takes on responsibilities quite frightening for such a young boy. Inspired to write the series as a way to give middle-grade readers substantive stories all their own, Thompson has nonetheless crafted a narrative that will captivate bookworms of every age.

Among other things, the Arcanium series explores the symbolism of different animals, including crows, wolves, and serpents. What do crows symbolize for you?

Where I live in Ottawa, Canada, there is a huge flock of crows that roosts near one of the hospitals throughout the fall and winter. Every morning, you can see them fly across the sky in long, waving rivers as they head out to the edges of the city to search for food. And every night, the process reverses itself, and you can watch those same rivers going the other way as they all fly back to that central roost for the night. It’s just a beautiful thing to see, and I’ve been known to drop whatever I’m doing at the time to just stand there watching that river of crows cross the sky.

In terms of the books, though, the crows are very much a symbol of pain and fear and loss. The villain in the books, Gideon Blackthorn, has a personal army of enchanted crows that are completely loyal to him. A great many of these crow-soldiers are kidnapped children that Gideon has transformed into birds and then enslaved. So, the people of Arcania have a very complicated relationship with these crows — they’re utterly terrified of them, but they’re also afraid to fight them because harming the crows could mean harming transformed children who cannot refuse Gideon’s orders because they’ve been enchanted to obey his every command.

But I went with crows because they’re so fascinating. They do have an ominous mythos around them, and a lot of old tales from all around the world present crows as harbingers of death or evil. But in reality, they’re also really smart birds. I loved that duality. It made them perfect for the story I wanted to tell.

Did any particular YA fantasy novels inspire the Arcanium series?

I think, throughout my life, the books that I’ve most enjoyed as a reader are the ones that have an ensemble cast where even the secondary characters are so well fleshed out that they feel as real as the main character does. I really loved David Eddings’ Belgariad and Mallorean books for that. I also read them because that world had a very richly defined history that occurred long before the story that was currently being told, and I think that helped to make that whole story feel so real, so compelling.

I really enjoy having more than one character to get attached to and root for, and I love exploring how everyone’s different personalities and unique talents can both cause some friction within the group and also help make the group stronger. I guess that’s probably why my books are told from multiple characters’ points of view. Ty is the main character, so you mostly get things from his perspective, but you also get to experience the world through other characters’ eyes — even the villains’, at times.

What was your favorite part about writing this book? And why do you feel drawn to YA novels?

My favorite part of writing the first book was watching the friendships growing between all the kids — they are all so different, but they’re very much a team…In my writing, I seem to be drawn to that grey area between middle grade and young adult. When my oldest was small, he was reading far above his grade level, and I had such a hard time finding books that were both age-appropriate but also geared toward a more advanced reader who wanted a more complex and nuanced story. I think maybe my love for this niche came from that time — wanting to write the kind of book I wished I could find for him. One of the most appealing things I find about writing for this age range is that we can help kids explore some of the really big things in life. We can show that the world can be dark and scary and unfair sometimes — because it absolutely can be, and hiding that fact from kids does them a disservice, I think. But, through stories, we can help kids understand how to process and deal with that and find agency in a world that sometimes makes us feel like we have none.

In what ways does the world of Arcania reflect reality?

Stories are one of the best methods we have for getting us to really think about what’s happening in our own world and how we want to shape it. The bulk of River of Crows was completed in the years immediately following America’s 2016 election and, from a non-American perspective, I think a lot of us who had never really paid much attention to politics before suddenly found ourselves taking a much closer look at what was happening in our own countries. I think a lot of the more political themes in the book were born out of that. There is also an environmental theme woven into the series that is just hinted at in the first couple of books but which becomes more prominent as the series progresses. Beyond that, there’s a very diverse cast of characters because the world is diverse. And I wanted that diversity to be the norm in Arcania.

What’s next for you?

My main focus for the foreseeable future is to finish the Arcanium saga, and then I have another series planned around a new world and new set of characters. Book three of the Arcanium, Stone of Serpents, should be out this spring. Book two [Mirror of Wolves] ends on a pretty significant cliffhanger, and Stone of Serpents picks up right where it left off. There are some major twists with this one that are going to change everything for our intrepid Team Arcania, and it’s really going to shake all of these characters up and affect their relationships with each other as they head into book four.