By Jakob Cansler

This article was originally published in the DC Line here.

Eleven years ago, celebrated Ukrainian playwright Sasha Denisova won Russia’s highest theater prize. That play was one of 25 she has produced in Moscow.

Today, though, none of her plays are performed there, or anywhere in Russia for that matter.

Denisova fled Moscow for Poland shortly after Russia’s invasion of Ukraine in February 2022; since then, she has focused her work on the war, having written and staged four new plays. The world premiere of one of them, My Mama and the Full-Scale Invasion, runs through Oct. 8 at Woolly Mammoth Theatre Company in a co-production with Philadelphia’s Wilma Theater, where the show will be produced early next year.

Denisova specializes in political theater that combines documentary with fantasy, and My Mama certainly fits that bill, with the script inspired by — and, in some sections, taken verbatim from — conversations the playwright had with her mother, Olga.

At 82, Olga decided to stay in Kyiv, where she has lived her whole life, amid Russia’s onslaught on Ukraine, including her city. That puts Olga on the frontlines of the war, both literally and in Denisova’s imagination.

At one point in the play, Olga tells her daughter that Russian soldiers are making their way to the “decision-maker.”

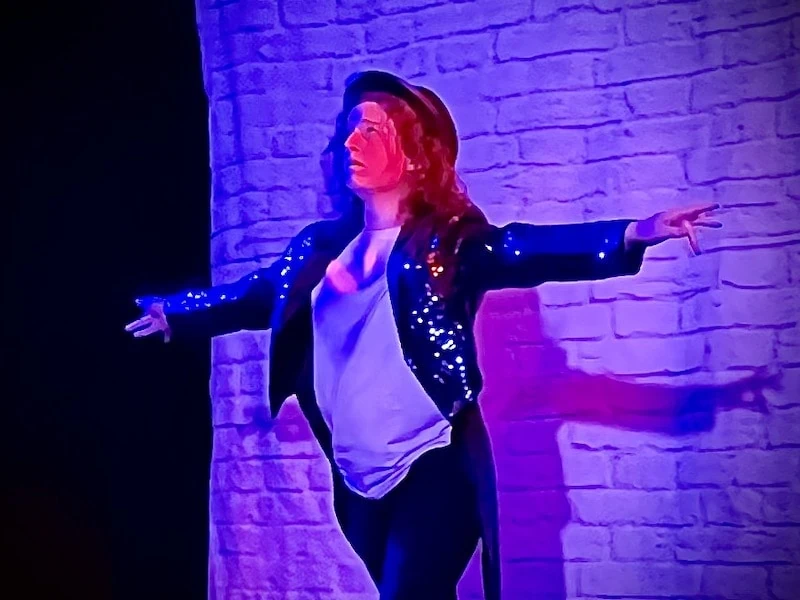

“Apparently my mama regards herself as the decision-maker,” Sasha, played by Suli Holum in the show, says in response. In the increasingly fantastical scenarios that follow, Olga strategizes with Ukraine President Volodymyr Zelenskyy, flies a fighter jet and converses with other world leaders.

The play “is a combination of a document and of a fantastic world,” Yury Urnov, the show’s director, said in an interview. “So the biggest — in a good way — challenge was how to give space to both of these, the real reality and fantastic reality on stage and how they can coexist.”

The two extremes also make for a play that is tonally complex, as over-the-top comedic sequences segue into moments depicting the harsh realities of war. In one section, a lighthearted moment of song and dance is cut off by a nighttime air raid.

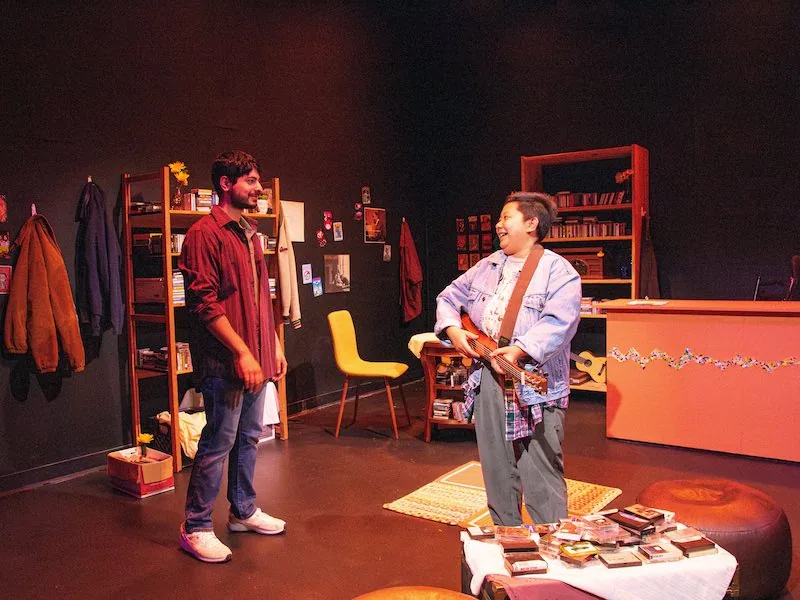

Denisova, Urnov and the rest of the creative team had to find a way to strike the right balance among all of these different elements. The result is a production that features a rotating set piece, a soundtrack that ranges from classical music to disco, approximately 100 custom-made projections, actor Lindsay Smiling playing a dozen characters, and deepfakes of the leaders of France and Germany.

Fitting all of that into a 90-minute play, and to make it cohesive, is challenging enough, but My Mama also had to be translated from Denisova’s native Russian.

“We had like a group of five people — bilingual and American, and Sasha, certainly — in presence who were pretty much going line by line through this play and and trying to make it work in English,” Urnov said. “It’s not just about the words, it’s about the contexts. It’s about the associations that resonate with English-speaking audiences.”

For the creative team, the drive to overcome these challenges wasn’t just an artistic responsibility. A play like this comes with political and social responsibilities, too, which raises the stakes.

More than a year and a half after Russia invaded Ukraine, during which time U.S. news coverage of the war has waned, My Mama serves as an explicit reminder of the toll Russia’s invasion has taken on Ukrainians. For Urnov, who was born and raised in Russia, the responsibility also feels personal.

“We are at a place where Putin’s regime is doing everything to normalize [the war]. There is a danger in the normalization of that,” he said. “We’re opening in DC. I think that’s the place where it needs to open. I hope people who can — who are politicians and the people who affect politicians’ decisions — will come and see it.”

And yet, to say that My Mama is simply a play about the war in Ukraine would be a mischaracterization. Much of it focuses on Olga’s life and her relationship with her daughter. Their dynamic is complicated, sometimes even antagonistic — and it shifts amid the war and after Olga decides to stay in Kyiv.

“At the heart of the play, really, is a mother’s love — not only for her child, but for her country,” said actor Holly Twyford, who plays Olga. “And she says I’m not going anywhere. And don’t you dare come here. And that is very powerful. I think it’s very powerful.”

After all, what most American media covers of the war is strategic, logistical or political — offensives and counteroffensives, bombing reports, document leaks, summits, aid deals. What is lost in that kind of reporting is the story of what it’s like for the Ukrainians on the ground, which is exactly what My Mama conveys.

As Twyford describes it, the play has both a “micro human element and very macro human element,” telling the story of Ukraine and the war through one woman’s thoughts and experiences.

“It will absolutely make you laugh, but it also won’t make you forget the reality of the situation. And I think that’s, I don’t know, that’s kind of the definition of hope, isn’t it?”