By Olivia Kozlevcar

This article was first published in Washington Independent Review of Books here.

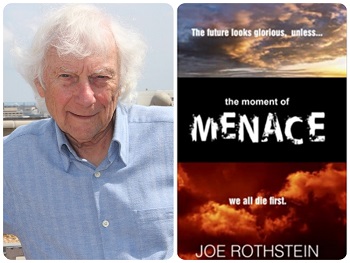

It takes a cognizant, careful writer to create works that honor the lives of ordinary people thrown into political and cultural turmoil. Marilyn Oser, author of the new novel This Storied Land, is such an author. This Storied Land tells the tale of a small circle of people living in Palestine during the British Mandate, and how their lives are shaped by it.

This novel is historical fiction that moves through a number of years in the early 20th century. How much research went into writing it?

My novels ordinarily have their beginnings with a question or a problem that I want to answer. In the case of This Storied Land, I wanted to know what happened in Palestine during the British Mandate, 1920-48. How did the conflict affect ordinary people’s lives — a farmer, say, or a laundress, a partisan, a nurse, a student. I started in my usual way, by reading novels of or about the period to see how fiction had treated the subject and whether I had something to add. I did. The novels written in the 1950s — Exodus, The Haj — provided an introduction to the issues but proved way too one-sided, favoring the Jewish settlers, ignoring or belittling Arab culture. (I use the term Arab or Arabic rather than Palestinian for clarity since Jews, too, were considered Palestinians at the time.) I moved to novels by Israeli authors, including S.Y. Agnon, Amos Oz, and Meir Shalev. (If you’re looking for a good read, by the way, I recommend Shalev’s Two She-Bears).

I had a deep background in Zionism through the research I’d done for my blog, Streets of Israel, which provides information about the people behind the street names of Tel Aviv, Haifa, and Jerusalem. Now, I began reading and taking notes from histories written by Israeli, British, and (current) Palestinian scholars. Not surprisingly, I became thoroughly confused amid a welter of conflicting claims by classical, revisionist, and post-revisionist scholars. What was the god’s honest truth? The same quandary has arisen in my research for two of my previous novels, Rivka’s War, set during World War I, and November to July, set at the Paris Peace Conference. Experience told me that, sooner or later, the wheat would separate from the chaff, and I would have facts that I could rely on by the weight of the evidence.

I continued to search out novels written during the period, as well as memoirs of that time, since those were the most likely to provide the little details that bring a story to life — what people were eating, or what cigarettes they were smoking, how they bought their food, what games the children played, what families did on outings at the beach. These were general impressions. Once I began writing, I used the internet to look up specific pieces of information that I needed. It was an online source when I was researching Rivka’s War that told me the color and texture of the soil in Ukraine, a detail I needed when Rivka dug a garden. In This Storied Land, to depict the Palestine Broadcasting System’s first moments on air, I used the internet to search out radios being produced in Europe circa 1936: what they looked like, how much they cost, which ones were available in Palestine.

My major research was finished by the time I started writing. By then, I had a good sense of the daily lives and concerns of Jews, Arabs, and Britons, and what they would confront. Over my two years of facing the page each day, I continued looking for specific bits of information; went on reading work by Jewish and Arabic poets and essayists; sought out photographs and watched [historical] videos to deepen my sense of the times; and listened to traditional Middle Eastern music, especially the oud, a stringed instrument of great emotional depth.

With This Storied Land, what responsibility did you feel in terms of depicting the history of Israel and Palestine accurately?

In the summer of 2019, I was hiking in the Caucasus Mountains when I fell into a conversation with a fellow hiker whose familiarity with the Palestinian Nakba (catastrophe) was far greater than my own. What she told me was food for thought that I kept chewing over long after the trip was done. Part of the impetus for writing this novel was my intention to do justice to the plight of the Arabs. I like to call my style of writing “history forward.” I feel a responsibility — no, an obligation — to my reader to get the facts right and portray the history faithfully in its effect on ordinary people. When the course of the narrative demands that I invent a fiction, I try for a workaround wherever I can, and usually I find one. I’m aware of only one factual change I made in This Storied Land: I moved up the destruction of an Arab village by one month to suit the demands of the narrative. Other than that — and a typo in Ben-Gurion’s date of death — I believe that the history I’ve depicted is accurate, and I think the story I tell is more compelling because of it.

You split the story up in sections, sort of like vignettes, some of which include definitions and clarifications. Why?

When I told an Israeli friend of mine that I was working on a novel set in Palestine, she hesitated — mused — [and] then said, “You can’t.” I laughed, wondering what she meant. But once I started doing my research in earnest, I discovered how extraordinary these times were. Things of consequence happened virtually every day, and Arabs, Jews, and Britons found themselves locked in an ever-shifting, toxic triangle. Meanwhile, world events weighed ever more heavily on them all — along with a trail of history going back into antiquity. Since I wasn’t up for a thousand-page tome with long expository passages, I needed a way to bring in a lot of information in an economical format. I was stumped.

Then, while reading Colum McCann’s Apeirogon, I realized I could adapt a technique he used to encompass the current Israeli-Palestinian morass. I began looking for allusive quotations to incorporate into the narrative — from newspapers, the Old Testament, the Qu’ran, Jewish and Arabic poetry, eyewitness accounts, and bits of knowledge from the science and the arts of the period. Employing this narrative structure enabled me to tell a multifaceted story in just 285 pages. It also provided thematic material. Schrödinger’s Cat was one of the scientific breakthroughs I included in This Storied Land; another was Einstein’s entangled particles. I was able to use Schrödinger’s conceptualization of being simultaneously dead and not dead as a metaphor in the novel, and to play with Einstein’s concept of entanglement in various ways involving people and things.

What’s next?

For the first time since starting Rivka’s War, I don’t know what will come next. I haven’t had much leisure in the last several years for recreational reading. I’m going to spend the next six months catching up on my long list of books to enjoy, while playing around with ideas for future writing of