By Thais Carrion

This article was originally published in Washington Independent Review of Books here.

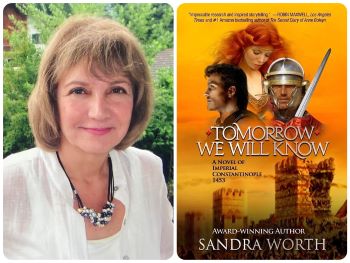

Sandra Worth’s most recent novel, Tomorrow We Will Know, is an epic situated during the fall of Imperial Constantinople and told through the romance between Emperor Constantine and Zoe, the daughter of his grand duke. Navigating this tumultuous period and the personal stories of three main characters, Worth weaves a riveting tapestry of the love that drove the actions at the heart of Constantinople’s fall. The familiar tale of the cowardice at the root of the city’s end is turned here into one of intense bravery and emotion that considers the humanity behind the events that took place.

Tomorrow We Will Know unfolds in a rapidly changing Constantinople. What inspired you to turn your attention to this time and place?

I first became intrigued by Constantinople when I read mention of the mysterious light phenomena that had plagued the city in the last days of its existence — phenomena that still baffle modern scientists. All I knew then about the ancient city was that it had been the seat of the Roman Empire for 1,100 years and was all that remained of that great civilization when it fell. Years later, I came across another mention of Constantinople, and an image of fire, death, and crumbling walls flashed into my mind. I began to read about the period, and the more I read, the more engaged I became.

The novel explores these events through the lens of a love triangle between Zoe, Constantine, and Justiniani. How did you develop their stories? And were there any characters that you found especially intriguing to write about?

All my novels are set in wartime and driven by the love story, because war is dark, and love is the only light. Sometimes, the love story is writ large in the historical record, but sometimes it’s buried, as it was with Constantinople. The picture that emerged — the love triangle — surprised even me.

Emperor Constantine’s story is a matter of record. When he wept for his people, his ministers witnessed his tears. We know his character and his hopes and dreams. We know he was a man of great courage who refused to flee his country, though his ministers begged him to leave. Into this dangerous world hovering on the edge of extinction came brave, dashing, princely Justiniani for the noblest of reasons. He was closer to Zoe’s age than Emperor Constantine. It was a time of crisis. Did he fall in love with her? How did Zoe feel about him?

I modeled Zoe’s character on what was known of her in Venice. She had a good heart, was generous, resourceful, and of high intellect, with a literary bent. I found nothing to indicate a relationship of any kind between her and Justiniani, but that is not surprising. Affairs of the heart were more likely to fuel gossip than record-keeping.

You ask about an especially intriguing character, and that has to be Justiniani. Constantinople was expected to fall within days to the Ottomans, but Justiniani changed that. Thanks to his courage, charisma, and military brilliance, 5,000 men withstood 150,000 enemies for seven weeks and nearly won an unwinnable war. Yet Justiniani abandoned his post just as the sultan was about to call the final retreat and Constantinople was about to win the war.

How did you tackle narrowing down the scope of this story?

As significant, momentous, and far-reaching as time has proved this historical event to be, the people in this extraordinary tale are what I focused on. History offers a stunning backdrop to the story, but it is the human heart and the resilience of the human spirit that I find awe-inspiring. Turkey won. They went on to win for a very long time. It took Europe 125 years after the fall of Constantinople to win its first victory against the Ottomans. It took Europe another 125 years to finally liberate itself from the threat of annihilation. Only Justiniani and a few brave Italians answered the emperor’s call for help. My book salutes their valor.

Your novel intertwines fiction with real events. How do you navigate the line between staying true to historical events and incorporating imaginative elements to engage readers?

Historical accuracy is always paramount for me because my readers expect it. Sometimes, there are conflicts in the historical accounts, and I’m obliged to choose which to follow. But when I have to fill empty spaces, I always strive to connect the dots between the events as plausibly as I can because I’m searching for the way it really happened. In the case of Constantinople, there weren’t any blank historical spaces to fill that I can recall. Except for Justiniani’s motivation at the end, we know from the diaries and writings of the many survivors precisely what happened. Only romance left wide blank spaces free for my imagination.

More relevant to storytelling is the need to keep the reader engaged by creating drama. I didn’t find that difficult here. Those who came before us lived with an appalling amount of drama in their lives. How they dealt with it and kept going when we ourselves might have given up is what keeps me enthralled. It all comes down to the resilience of the human spirit. They may have won the battle and lost the war, but even across the ages, their deeds blaze with light and warm the heart. They deserve to be celebrated. Even 600 years later, they have something to teach us. We can learn from their fortitude when we face our own battles in our modern life.