By Daarel Burnette II

This article was originally published in DC Theater Arts here.

What should we do with all the cultural vestiges of America’s racist past?

Today, the clothing, language, and statues that were created to assemble and glue together a system that subjugated Black people litter our day-to-day lives in sometimes embarrassing ways.

Do we ignore these cultural vestiges, hold onto them as a haunting reminder of our past, or expunge them as a way to combat contemporary forms of racism?

Monumental Travesties, written by Psalmayene 24 and directed by Reginald L. Douglas, now being shown by Mosaic Theater Company at Atlas Performing Arts Center, aptly tackles this provocative question in a tightly wound comedic plot.

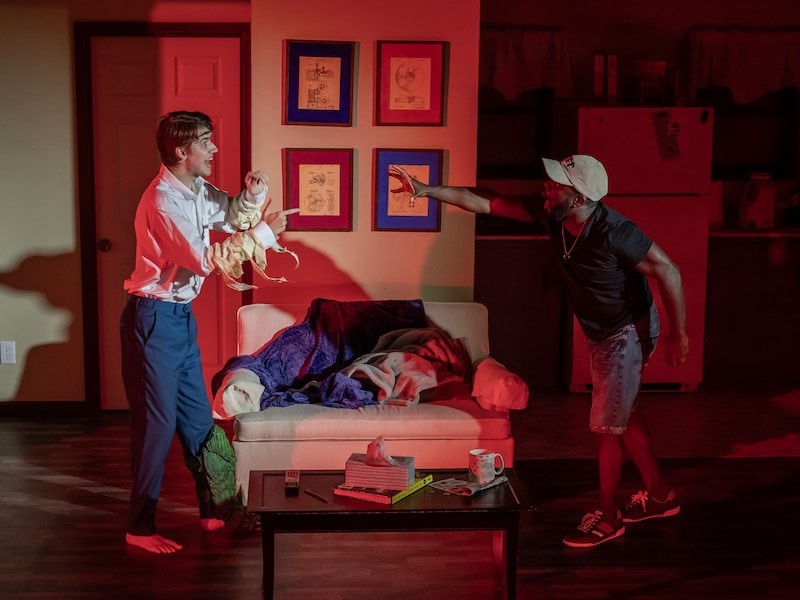

The world-premiere play is delivered with a punch by Louis E. Davis, Jonathan Feuer, and Renee Elizabeth Wilson, standout stars who at times left their majority white spectators visibly squirming.

Louis E. Davis as Chance, Jonathan Feuer as Adam, and Renee Elizabeth Wilson as Brenda in ‘Monumental Travesties.’ Photo by Chris Banks.

Psalmayene 24 centers his plot around Thomas Ball’s Emancipation Memorial, a statue that has been controversial since freed slaves raised money to erect it in 1876.

The statue depicts a larger-than-life Lincoln standing over and “freeing” a mostly naked and kneeling Black man, whose feet are wrapped with a ball and chain.

We learn at the beginning of Monumental Travesties that Chance, played by Davis, has climbed the statue in the middle of the night, sawed off Lincoln’s head, and, being chased by the cops, dumped it in the garden of his white next-door neighbor Adam, played by Feuer.

In most plays about racism, playwrights require their Black characters to grapple with the many ways racism knocks at their confidence, warps their perceptions, tangles up their family lives. White characters are tasked with being a bit less racist.

But in Monumental Travesties, Psalmayene 24 flips this model on its head.

Adam is having a full-blown identity crisis, wracked by what he sees as whiteness destroying the world and feeling compelled to shed his white identity. A recent bout with COVID has apparently depleted his memory.

Chance and Brenda, played by Wilson, are confident with their Black identity, as is evident in the set, designed by Andrew Cohen, which features African print, furniture, and pottery, and Jean-Michel Basquiat art. But their marriage has recently been sexless. Brenda is underemployed and Chance has decided to quit his job to be a full-time radical performance artist. They somehow are able to afford a gentrified home in DC.

In this wonder of a script, Psalmayene 24 gives his characters lines that are poetic and biting and knee-slapping funny. He punches up at the sometimes surprising reactions white people had to George Floyd’s murder and their insistence that we scrub our society of language that looks and feels racist — the same white folks who were then less bullish when it came to changing racist policies.

Davis, Feuer, and Wilson deliver their lines with comedic perfection. They throw their entire bodies into their characters, play off the audience’s shock.

Feuer especially is unafraid to delve into the darker aspects of white identity and delivers some of the play’s most piercing lines.

Costume designer Moyenda Kulemeka found some of the most interesting and appropriate outfits for Chance and Adam. Outfits that scream, “I’m not a racist.” And outfits that scream, “Black people don’t belong here.”

I have a few quibbles: the head of the Lincoln statue was at times treated as if it was heavy; at other times, as if it was light. Davis, whose hair is dyed neon green, performs at a level 10 for most of the play, when sometimes it requires his character to be at a level six. And some of the characters’ time off stage to grab one or two items seemed excessive. Nothing that can’t be ironed out.

At the beginning of the production I attended, Douglas, who serves as Mosaic’s artistic director, said he wants Mosaic to be a “catalyst for change and community building.”

With Monumental Travesties, Mosaic hit the bullseye.