By Daarel Burnette II

This article was originally published in DC Theater Arts here.

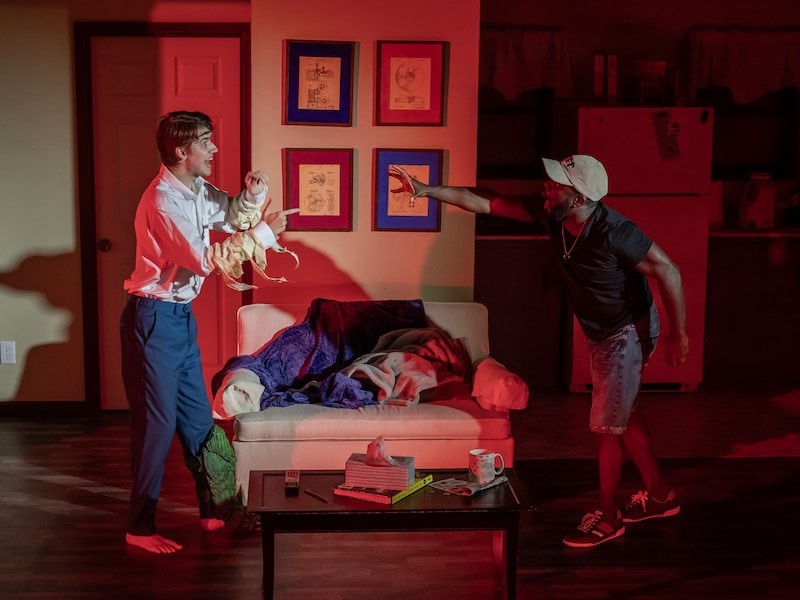

Actor Fletcher Lowe makes a mean monster. He sprawls his limbs, curls his fingers, and makes a guttural noise so freakish I squirmed.

It’s too bad that the plot of Monsters of the American Cinema — presented by Prologue Theatre at Atlas Performing Arts Center through August 6 — fails to make much sense of his character Pup’s monstrous tendencies. There are moments throughout this 90-minute play, directed by Jason Tamborini, co-starring Gerrad Alex Taylor as Remy Washington, that were intimate, frightening, funny, and sad. But the dots are never connected for me to make sense of it all. The stakes are never raised enough for me to care.

Playwright Christian St. Croix stuffs a kaleidoscope of identities with fraught pasts into two characters, parsing out their backstories in a series of monologues.

Remy is a Black gay man who fled his abusive family and the racist South to work in San Diego, where he meets and falls in love and marries Pup’s father, who soon dies of a heroin overdose and leaves Remy his drive-in movie theater and straight, white teenage son, beset with recurring nightmares, to look after.

Pup and Remy bond over their love and deep knowledge of 1930s horror films, clips of which are projected on two giant screens that border the stage.

Scenic designer Nadir Bey assembled an elaborate set, giving us a glance at Pup’s messy room, walled off from a neat living room and kitchen. Two-thirds of the way through, the characters move to the roof of the set, which doubles as the drive-in.

The set is enhanced by designer Helen Garcia-Alton’s lighting, which flashes from the ground and the sky and the sides of the stage, and sound designer Dan Deiter, who projects pounding noises that make the seats shake.

Pup and Remy crisscross the set, entering and exiting, pausing to give long monologues before interacting with each other. This can be hard to follow for the average theatergoer who can handle only so much information and subplots at once. Are we supposed to pay attention to Pup’s growing racism and homophobia? Or his nightmares? Or Remy’s struggles to take care of Pup and the drive-in? All three?

Taylor lands some funny jokes through his characterization of Remy.

And the bonding and intimacy displayed between Pup and Remy is poignant and convincing. Remy’s arms are tangled up with Pup’s as they wrestle over a cell phone. Remy bounces on Pup’s bed as he plays Candy Crush.

But I wasn’t convinced, honestly speaking, by Remy’s reaction to the moments Pup used the F and N words, a lazy way to indicate that Pup loves his stepfather but is disgusted by his identity (being called a slur, while hurtful, is not the most typical or potent form of racism and homophobia for Black gay people).

The highlight of this show is Lowe’s acting, who would shine in a play about monsters that made more sense.

No Comments