By Samantha Neugebauer

This article was originally published in DCTrending here.

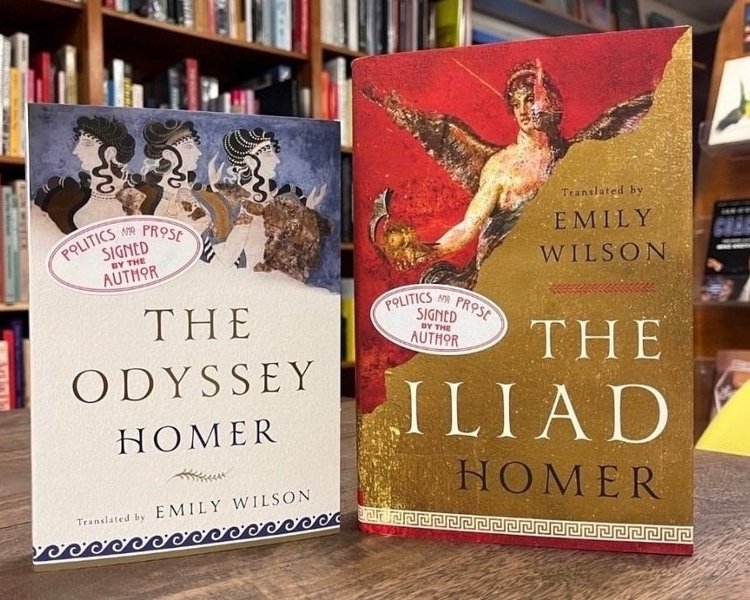

It was standing room only at Politics and Prose on Sunday for an event with Emily Wilson, acclaimed translator of Homer’s Odyssey and, most recently, The Iliad. With a deep and frightening cadence, Wilson began by reciting the ancient text in its original Greek, and a pin drop could be heard throughout the crowded aisles as attendees were transported to a time of the Trojan War. Eventually, however, after too short a time, Wilson broke the spell she set over the bookstore by switching back to English.

For Wilson, who lives in Philadelphia and is a professor of classical studies at the University of Pennsylvania, contemporary readers of Homer need to undergo the sonic and rhythm experience of his text as much as the narrative experience. For this reason, in both her Homer translations, she uses iambic pentameter (da-DUM da-DUM da-DUM…) instead of the free verse preferred by many other renowned English translators. In her forward to the Iliad, released this October, Wilson explained that “Ancient Greek verse did not rhyme, but it always used regular rhythm” and that “sonic patterns were created by the length of syllables, rather than by patterns of stress, as in English verse.” She believes that the iambic pentameter is our closest equivalent to the original’s dactylic hexameter. Indeed, English speakers often enjoy verse in iambic pentameter; its musicality not only reminds us of Shakespeare but also of our heartbeat. As a result of Wilson’s metrical choice, her short lines are straightforward yet mighty, mimicking Homer’s lineation.

See Wilson’s opening compared to noteworthy translations by Alexander Pope and Richmond Lattimore.

Wilson

The Quarrel

Goddess, sing of the cataclysmic wrath

of great Achilles, son of Peleus

which caused the Greeks immeasurable pain

and sent so many noble sons of heroes

to Hades, and made men the spoils of dogs…

Pop

Argument

The Contention of Achilles and Agamemnon.

In the war of Troy, the Greeks having sacked some of

the neighbouring towns, and taken from thence two beautiful

captives, Chryseis and Briseis, allotted the first to Agamemnon,

and the last to Achilles…

Lattimore

Sing, goddess, the anger of Peleus’ son Achilles

and its devastation, which put pains thousand-fold upon the

Achaians, hurled in their multitudes to the house of Hades strong souls

of heroes, but gave their bodies to be the delicate feasting

of dogs, of all birds, and the will of Zeus was accomplished

In Wilson’s telling, her reverence for English literature and anglophone metrical poetry tends to set her apart from other classists. At the event, she detailed her academic background, describing how she and her work are the product of interdisciplinary studies. She holds a Ph.D. in Classics and Comparative Literature from Yale, and a B.A. in Classics, and an M.Phil. in Renaissance English Literature from Oxford.

“Most people trained in the classics,” she said, “are not as interested in the tradition of English literature as I am.” It’s perhaps not surprising then that Wilson appears interested in the development of the English language and doesn’t shy away from employing modern language and syntax in her translations: “He will not come home/ from the war and cruel conflict, and his children/ will never clutch his legs and call him Daddy.” In general, Wilson sought to capture the “folk-poetry feel of the original.” Simultaneously, however, Wilson doesn’t aim for overt vernacularism. She likes some artifice, she says, and avoids contradictions in her translation.

A lot has been made about Emily Wilson being the first woman to translate the Odyssey, however, for Wilson, that fact is not as essential as the media makes it out to be. Frankly, it’s refreshing to see a creator gesture toward the merits of their creative and intellectual choices over the personal biography. At the same time, she told the audience that this does not mean she is uninterested in discussing what’s going on with gender within Homer. She very much welcomes that discussion.

Near the program’s conclusion, an attendee asked Wilson if she considered The Iliad an anti-war poem. Wilson responded that she doesn’t think it’s a “pacific book.” Moreover, she says, that while it’s true that the text does not imagine a world without conflict, it does imagine ways that society may not have to be as deadly. Nevertheless, The Iliad is a violent book; it’s a story where life and death stakes marked page after page, where the human body is constantly being unknotted.

While the book’s violence might seem to some relevant, the audience was looking for why to revisit this ancient text; Wilson doesn’t care about ‘relevance’ either. On Twitter, Wilson commented: “When people ask me about the “Eternal Relevance of The Iliad”, I sometimes say: read it because it’s not relevant. The human experience is so much bigger than here and now.”