by Samantha Neugebauer

This article was originally published in DCTRENDING, here.

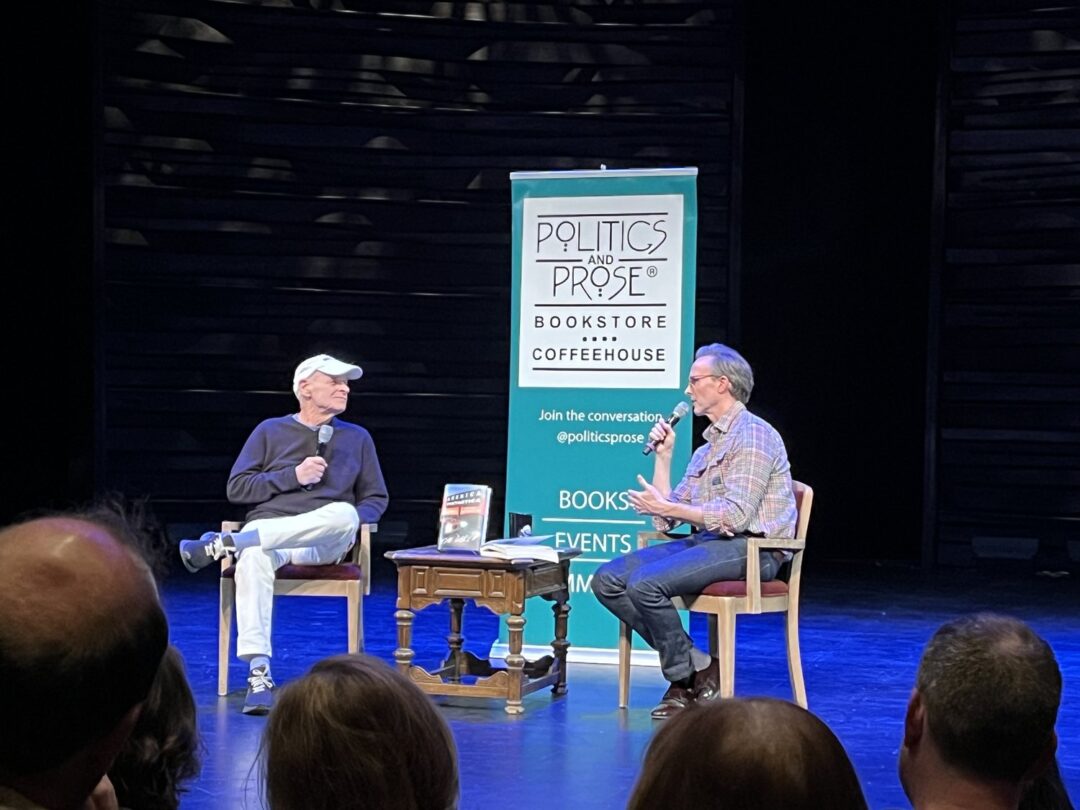

Acclaimed author Tim O’Brien sat down with Claiborne Smith, the literary director of the Library of Congress, at Arena Stage to discuss his new novel, America Fantastica. The event, hosted by Politics and Prose Bookstore, was the first stop on O’Brien’s book tour. He used the program as an opportunity to discuss the genesis of his new book, his first in twenty years, and meditate on the state of American culture.

Since the latter half of the twentieth century, O’Brien has remained a steady presence in American letters. Among other accolades, he received the 1979 National Book Award for his novel Going After Cacciato and the 1995 Society of American Historians Prize for Historical Fiction for In the Lake of the Woods. Yet, it’s his 1990 Pulitzer-Finalist masterpiece The Things They Carried, a collection of linked stories about a platoon of American soldiers during the Vietnam War, that most people know O’Brien for and which earned him his spot in the American literary pantheon. Since its publication, its first chapter has been widely anthologized and regularly assigned in English classrooms across the country, serving as an entryway to understanding the psychology of the soldiers in that gruesome war for generations of American students. The novel’s significance is especially felt for members of my generation (millennials) whose parents may or may not have been deployed to Vietnam and whose high school history classes tended to focus on the domestic transformations occurring during those decades rather than the soldiers’ stories themselves if we reached the back of our textbooks at all.

During the interview, O’Brien was questioned about the long interlude since his last book, and he explained that he’d started America Fantastica years ago and abandoned it. Although one main character, Angie Bing, haunted his life (including appearing at the dining table with his wife and children), he was more focused on fatherhood than finding the story. He returned to the concept (and Angie) when he could no longer take our lying culture. O’Brien jokingly exclaimed: “It might be my old age, but with everything, our banks, our airlines – everyone is lying. You call anywhere, and they say, Our lines are hectic,’ but that’s not true. They’re always busy. It’s a lie, and we’ve learned to live with it, and all these lies are adding up. That was the germ of the novel.”

During this incubation time, O’Brien stumbled upon the term ‘mythomania,’ which he described as the epidemic of lying that has infected the American people. “You can’t beat the liars with rationality,” O’Brien said, “Rationality is irrelevant.” For this reason, he decided America Fantastica would be a satirical novel in the tradition of Jonathan Swift and Mark Twain. As an example of the kind of zany, irrational storytelling that he finds persuasive, he retold the story of Swift’s essay “A Modest Proposal,” in which the Anglo-Irish writer recommended that Irish peasants sell their children as food to the rich to ease their economic burdens. In doing so, the author pointed out the hypocrisies of the rich, who blamed the peasants for their financial hardships. It was a “funny response to a serious problem,” he said.

America Fantastica’s plot hinges on a hyperbolic series of manic choices and events, beginning with protagonist Boyd Halverson’s choice to rob a local California bank. Boyd is a compulsive liar and a disgraced former journalist turned JCPenny employee who decides to use his stolen money for one last road trip across the country, kidnapping bank teller Angie in the process. The novel also features many eclectic characters they meet along the way, including Angie’s jilted fiancé and Boyd’s ex-wife. Throughout the novel, Boyd tries to make sense of his life and separate the lies he’s told from reality.

Describing his novel, O’Brien seemed more interested in capturing what our lie-drenched world feels like today than parsing out why our culture has become what it has. At one point, circling a kind of diagnosis, he recited a verse from Yeat’s poem “The Snare’s Nest By My Window” concerning the 1922 Irish Civil War, which O’Brien used as one of his book’s epigraphs: “Whatever it is, the way you tell your story online can make all the difference.”

We had fed the heart on fantasies,

The heart’s grown brutal from the fare,

More substance in our enmities

Than in our love; oh, honey-bees

Come build in the empty house of the stare.

Several times, O’Brien spoke about the role of fantasy in our lives– “We need fantasy to get through the world,” he said. “We need to believe that tomorrow will be better. We all have fantasies about the afterlife. We believe we can live on after death through our children, through our good deeds, and our writing. That’s true in my case.” Boyd is no exception, either. In O’Brien’s telling, Boyd leads a “grim life” and “like a lot of America, he needs to replace his circumstances and his life outcomes with fantasy.”

Smith asked O’Brien what his novel can bring to this topic that non-fiction can’t. “Story,” replied O’Brien. For O’Brien, being a writer is like “holding a mirror” out to the world, while writing is like a “waking dreaming” where he enters a dream world that inserts itself over him. His writing routine begins early, around two in the morning; he starts by doing the dishes while his family is fast asleep, letting the “bumblebees of memory go through my head. “Some of the best dialogue I’ve written has been delivered to me,” O’Brien said. At the same time, as a novelist, O’Brien said he is thinking about psychology, social criticism, politics, and other subjects all the time. Yet, he also admitted that focusing too much on the topical or the present moment can be “the death sentence of a novelist.”

During the Q&A at the end of the night, an audience member announced that he had read The Things They Carried five or six times and that his children had read it, too. “It was one of the most important books I’ve ever read,” he said. Another attendee, a high school teacher, asked, “What else, besides your work, should I assign kids to read?” O’Brien’s recommendations were of the classic sort: Catcher in the Rye, The Great Gatsby, and Turgenev’s First Love. “Are kids still reading those?” he asked, laughing. His answer and his many other references to classic and ancient writers and thinkers — Socrates, Martin Luther, and the Illiad, to name a few – point to the way reading has shaped O’Brien’s life and worldview.

No Comments