By Haley Huchler

This article was originally published in the Washington Independent Review of Books here.

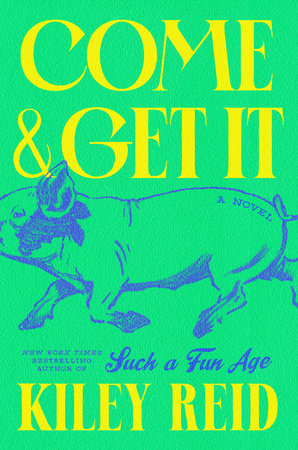

It’s nearly impossible for me to resist a good campus novel. Any setting that throws together people from different backgrounds and cultures is bound to create the sparks required for interesting literature. In Come & Get It, author Kiley Reid takes full advantage of her college locale to craft a drama fueled by the financial tensions her compelling, complicated characters endure.

Reid’s sophomore effort has been eagerly anticipated since the success of her debut, Such a Fun Age, about a young Black woman entangled in the lives of the wealthy white family she nannies for in Philadelphia. Come & Get It returns to the author’s fascination with issues of race, privilege, and class, this time at the University of Arkansas. The narrative alternates among the perspectives of three women: Millie, a student and resident assistant saving up to buy her own house; Agatha, a writer and visiting professor dealing with a recent breakup; and Kennedy, a transfer student struggling to adjust and make friends.

The story begins with Agatha interviewing three undergrads in Millie’s dorm for a book she’s writing on weddings. After they pepper her with anecdotes about “practice paychecks” from their parents and the “fun money” they earn at their campus jobs, though, Agatha leaves the interview more interested in the girls’ economic backgrounds. She enlists Millie’s help to continue listening in on the lives of these wealthy, out-of-touch students. Soon, both Agatha’s book project and her relationship with Millie get messy.

Abundant references to contemporary books, movies, and brands make the novel feel truly of-the-moment. Reid leaves the reader with no doubt that her story is anchored in a specific time and place. Birkenstocks, “Pitch Perfect 2,” and Victoria’s Secret all appear within the first two pages; Millie’s bookshelf holds Americanah, Sweetbitter, and The Omnivore’s Dilemma; and Kennedy’s homesickness is personified by her weeknight plan to watch “27 Dresses” while her mother simultaneously streams it at home. Such specificity makes the characters feel incredibly real; anyone who’s spent time at a Southern university in the past few years would recognize them instantly.

This plethora of detail falls in line with Reid’s style of writing. You can be sure upon meeting any character that you’ll soon know everything about them, from where they grew up to what they ate for breakfast last Tuesday. These details are particularly important in illustrating the financial tensions at the heart of the story. For example, we learn that much of Agatha’s incompatibility with her former partner stems from their out-of-sync spending habits, and that Millie’s desire to save for a home drives her every decision. In Come & Get It, everything comes back to finances. Unfortunately, it’s not always clear why.

Unexpected plot twists also make this a slightly darker book than readers might initially expect. In the first half of the novel, the stakes aren’t all that high — it feels almost like a character study — but a rapid turn of events shakes things up. While Reid certainly knows how to keep readers hooked, the story’s climax feels oddly disconnected from the book’s earlier acute emphasis on wealth (or lack thereof).

Despite the intense and unwavering focus Reid projects onto each character’s relationship with money, I can’t tell what she wants us to make of it all. Yes, Come & Get It presents a world divided by privilege and class, but it offers no conclusions. Getting to know Millie, Agatha, and Kennedy felt like peering into a zoo and being intrigued by the inhabitants’ understandable, sometimes deplorable behavior. You walk away entertained but unenlightened.

Nonetheless, it’s an enjoyable, easily digestible read with characters who’ll stick with you long after you’ve closed the book. And if you happen to be anywhere near an American college campus, you just may run into them.