Written by Hannah Berk

This article was first published in Tagg Magazine here.

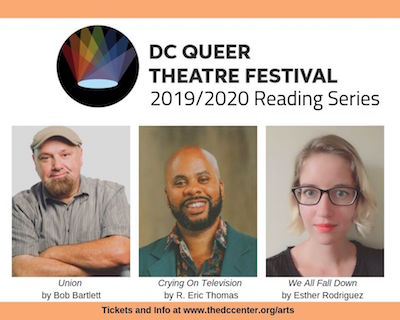

On November 23, the seventh annual D.C. Queer Theatre Festival will kick off with the first of three interactive table readings of brand new, unpublished plays by local LGBTQ artists. The festival guarantees that audiences will encounter work never before produced, and also offers a new way to engage with that work by providing pivotal feedback to the featured playwrights while their work is still in progress. “We like to change up the festival each year,” says Artistic Director and co-founder of the festival Matt Ripa, “to keep [it] fresh and to honor the different styles and work that queer artists are creating in the D.C. area. For this year’s festival, audiences can expect exciting new plays that are thought provoking and be the first to hear brand new scripts that might be on stages soon.”

This year’s plays were selected from among over 20 entries and represent a breadth of genre, from a comedy (R. Eric Thomas) to local history (Bob Bartlett) to a family drama (Esther Rodriguez). The winning playwrights have the opportunity to work with a professional director and dramaturg while they develop their scripts over the course of rehearsals. Finally, plays will be performed as staged table readings for the public.

Eric Thomas, “Crying on Television,” November 23, 2019 at 7 p.m.

Crying on Television, described as “a comedy about trying to make a connection through a screen,” centers themes of community, race, and our personal relationships with television. “I’m interested in having conversations about where people belong, where they don’t belong,” says playwright R. Eric Thomas. The theater is a well-suited venue for this kind of dialogue, and Thomas looks forward to the audience feedback element of the festival. “You learn so much when an audience watches a comedy,” he says. “It can be a communal experience. I’m hoping people walk away having conversations about community and the people they don’t normally think about much.”

Thomas wears many writer hats, including columnist at Elle.com, memoirist/essayist, and host of The Moth in Philadelphia and D.C. While his plays have been featured in several U.S. cities, including his hometown of Baltimore, Crying on Television marks his D.C. metro debut. “I’m excited to get more involved in the vibrant D.C. theater scene,” Thomas says. “Baltimore has a theater scene that doesn’t get enough credit, and D.C. is a place where a lot of really exciting, interesting things are happening.”

Bob Bartlett, “UNION,” December 7, 2019 at 7 p.m.

UNION will be Bob Bartlett’s second production with the DC Queer Theatre Festival, following his 2014 winning play about the export of violent homophobia from the U.S. to Uganda. Through UNION, Bartlett hopes to give audiences a fuller sense of Walt Whitman’s character and queerness. “My play considers his years living and loving in D.C. (and cruising Pennsylvania Avenue in a horse-drawn streetcar),” says Bartlett, “as well as his affinity for Lincoln and belief in the future of American democracy…I was most interested in exploring Whitman’s sexuality while he lived in our city and his attitudes about race, which were not unlike those of white men of the period.”

This play strikes a personal chord with Bartlett, who has long wanted to write about the poet’s D.C. years. “Like so many, I discovered Leaves of Grass in high school, and I’ve had a copy, multiple copies, with me since,” says Bartlett. “Expansive and audacious, to say the least, the book continues to inspire and even guide us…It was the first gay book I’d ever read.” For Bartlett, it’s meaningful to have this play debut at a festival that centers around the LGBTQ community. “While I believe UNION will resonate with all audiences, I hope that queer audiences experience the play on another level.”

Esther Rodriguez, “We All Fall Down,” February 22, 2020 at 7:00 pm

We All Fall Down centers a young woman navigating her family dynamics in the aftermath of a suicide attempt and the leadup to coming out. “Mental illness is something we don’t really talk about unless there’s a really visible suicide or attempt by a famous person,” Esther Rodriguez says. These stories are followed by a flurry of activity and information, but after the news cycle turns over, grief and trauma remain.

We All Fall Down is Rodriguez’s effort to keep the conversation going, and to bring it home for an intergenerational audience. A recent college graduate, she sees a shared understanding of mental health and a culture of support in her generation, while older generations seem to lack that level of comfort. “I wanted to give more of a voice to these kids who are reaching out and encountering resistance,” Rodriguez says, “not from a lack of desire to help” but from a culture of silence.