By Jakob Cansler

This article was originally published in DC Theater Arts here.

Theater has long been obsessed with magicians. For an industry in the business of creating compelling work, there is an understandable fascination, perhaps even jealousy, with the power a good magician can hold over an audience, with their ability to create a spectacle that denies — and allows the audience to escape — reality.

It is ironic, then, that Open, a one-woman show about a magician, has quite the opposite effect. Now performing at Nu Sass Productions, Open is a heartrending magic show light on escapism and heavy on reality.

The Magician at the center of this show is nameless, and notably not a magician. She is instead a woman desperate to deny reality. To do so, she imagines herself in a magic show, and uses tricks, albeit imaginary ones, to trace her relationship with her girlfriend, Jenny, and to understand how she ended up in the harrowing moment she is in now. Despite her best attempts, her memories flood back, in the form of voiceovers. Her reality, it seems, is impossible to deny, even as her imagination runs wild.

To be clear, that the entire show takes place in the Magician’s head is not a spoiler. She tells us as much within the first few minutes. She also informs us that we, the audience, are imaginary as well, that we exist in her head to make the magic show seem real. She demands applause when she turns an imaginary egg into an imaginary parrot, when she juggles imaginary balls, when she walks an imaginary tightrope. We, the imaginary audience, cheer her on.

That we are informed early on that we are imaginary creates an immediate connection between the audience and performer, since we are essentially in the show with her. With the level of intimacy at Nu Sass — the company performs in a small, converted art gallery — that connection is even more intense.

Intimacy also works well for a show like Open, which can be, at times, heavy-handed in its subject matter. In a small space, where it often feels like the Magician is talking directly to you and isn’t afraid to make eye contact, her sincerity is impactful. In a larger space, with less direct connection between the audience and performer, such frank discussion of these themes might not carry the same weight that it carries here.

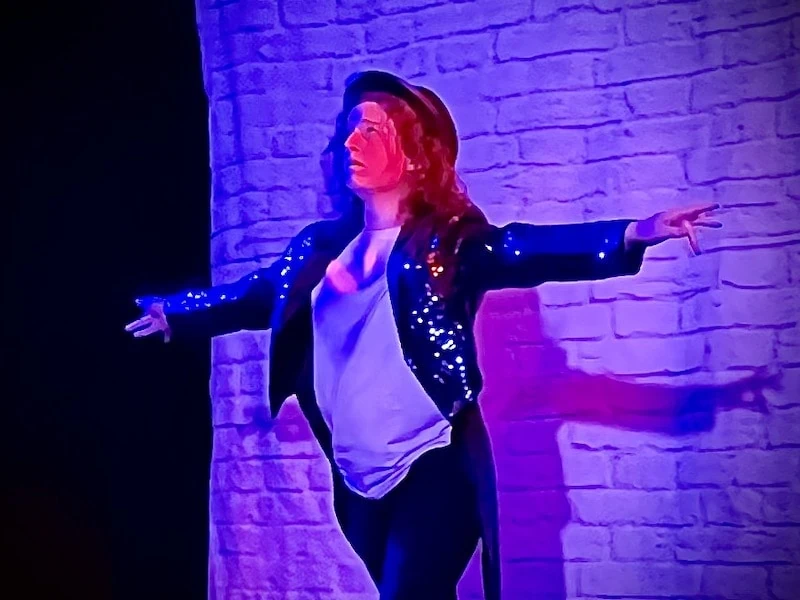

Allison McAlister’s performance as the Magician is certainly beneficial to that end. She strikes an impressive authenticity when conveying more distressing memories and emotions.

It is actually in the lighter moments of the show that McAllister could stand to be more intense. After all, Open takes place in the imagination and in a moment of desperation, and the frantic energy that often comes along with those qualities is missing here. When the Magician is candid, the desperation is there, but when she is in denial, she often seems too grounded. At times, it feels less like her imagination is running wild and more like her imagination has been carefully plotted.

Creating more variation in energy would also, presumably, speed the show’s pacing. As directed by Dom Ocampo, Open isn’t too long by any means — the runtime comes in at around only 80 minutes — but rather it relies too heavily on slow speeds to convey emotional pain. Variation would convey the wide range of emotions associated with a moment like the one the Magician is in, and in turn create a more compelling emotional arc.

Still, at the end of the day, the payoff that comes with following the Magician’s internal conflict through to the end comes through, and when it does, it hits hard. This is the kind of show where there is a gap between the final blackout and the applause because no one wants to be the one to break the tension.

In fact, there’s some irony in that blackout as well. Often, at a magic show, the loudest applause comes when the magician fools the audience, forcing them to, at least for a moment, pretend that the magic is real. In Open, the loudest applause comes when the Magician admits that it is not.