By Daarel Burnette II

This article was originally published in Dc Theater Arts on May 22, 2023, here.

In the spring of 2019, a protest broke out in a rapidly gentrifying neighborhood of Washington, DC, after a T-Mobile store owner was told by the police to turn down or off the clanging Go-Go music he’d blasted from outdoor speakers for decades.

Anger had been swelling for years over who in the neighborhood would have access to shrinking resources, who the police would police, and who the neighborhood really belonged to.

That scene has now been deftly brought to the stage by Studio Theatre in Good Bones,written by James Ijames and directed by Psalmayene 24.

The play forces its audience of mostly white DC residents to think critically about their own role in Black displacement and the sharing of space through the use of unsuspecting characters, the Black gentrifier.

Its acting is gripping, and the set is dynamic, though the plot is at times wanting.

Good Bones was commissioned in 2019 by Studio. Ijames, who recently won the Pulitzer Prize for Fat Ham, wrote the play based on his time in the neighborhoods around Studio Theatre and growing up in Philadelphia, according to Studio’s artistic director David Muse.

It adds to a growing genre of art that explores the Black gentrifier, who’s conflicted about their obligation to give back, their own understanding of “authentically Black,” and their newfound ability to afford.

Middle-class Black people are significantly more likely to live in low-income neighborhoods, according to a 2015 Stanford University study. This act is often spurred on by their attempts to escape anti-Black racism in white suburbs, deep kinship with family and friends in low-income neighborhoods, and bias embedded in the real estate industry. But it prevents Black children from accessing better schools and exacerbates the wealth gap, since homes in Black neighborhoods don’t accrue value the way they do in white neighborhoods.

In Good Bones, Aisha, played by Cara Ricketts, and her husband Travis, played by Joel Ashur, move into a fictionalized city undergoing a rapid demographic shift. Earl, a local contractor played by Johnny Ramey, questions the way Aisha talks, what she does and doesn’t know about the local neighborhood, and her attempt to revitalize the once-abandoned home, which is haunted.

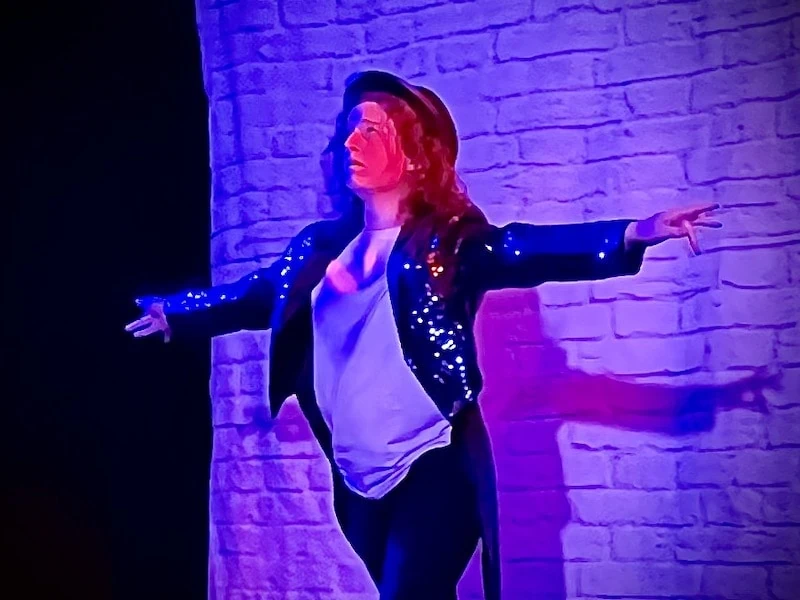

Ashur and Ricketts bring to the stage the sort of authentic chemistry that makes their newfound love believable. Their dance breaks, which co-stars lighting produced by William D’Eugenio, is both well coordinated and entertaining.

There were moments when I thought the plot could move beyond the sometimes-predictable frictions communities across the world experience when class and race clash. We’re only given glimpses at some characters’ backstories. Some of the monologues are redundant and plodding.

Nevertheless, sometimes it’s necessary to say over and over again to an audience that their actions have consequences. That makes Good Bones worth it.