By Jakob Cansler

This article was originally published in the DC Line here.

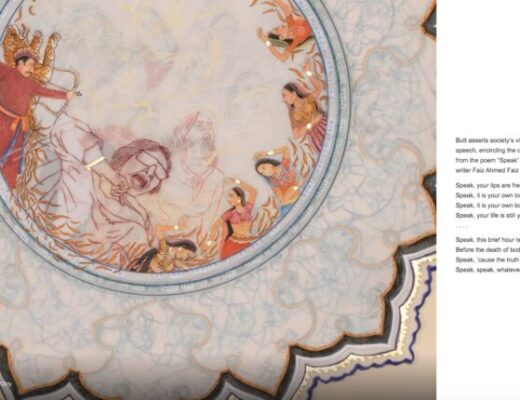

Tucked away in a small room on the third floor of the Art Museum of the Americas (AMA) is a series of works that all seem to be in dialogue with one another. Their media, style and color vary, but among them is a clue to their conversational starting point: a singular painting by Pablo Picasso.

The exhibit, titled Year of Picasso: A Dialog With the Americas, is being presented 50 years after Picasso’s death in 1973 and is one of dozens of exhibitions across Europe and North America celebrating the iconic artist.

Unlike most of the other shows taking place this year, though, the exhibition at the AMA — a contemporary Latin American and Caribbean art museum that is part of the Organization of American States (OAS) — is focused almost exclusively on how Picasso and his work influenced artists in the Americas throughout the 20th century.

In 1973, three years before the museum opened, the OAS held a tribute exhibition to Picasso featuring works from all of the organization’s member states. Although much smaller in size and scope, A Dialog With the Americas is inspired by that exhibition.

The featured Picasso work is “L’aubade,” which he created while living in German-occupied Paris. A cubist painting designed to highlight the feeling of imprisonment — and perhaps the slightest feeling of hope — of that time, “L’aubade” is a showcase of the ways in which Picasso influenced other artists both in style and in his belief that all art is political.

In some of the works in the AMA’s exhibition, those influences are obvious. Colombian artist Alejandro Obregon’s “The Dead Student (The Vigil)” has a composition that seems inspired by “L’aubade,” and features a similar style. Obregon created the work in 1956 as a protest against the police killing of a group of students in Bogotá two years earlier under the authoritarian government of Gen. Gustavo Rojas Pinilla.

“The Last Serenade,” a painting by Argentine artist Emilio Pettoruti, seems to be directly inspired by Picasso’s “The Three Musicians,” while Mexican artist José Luis Cuevas’ “Homage to Picasso: The Real Ladies of Avignon” is a direct response to one of Picasso’s most famous works — “The Young Ladies of Avignon,” which was seminal in the development of cubism. Cuevas’ work approaches a similar tableau but with a more exaggerated, almost grotesque style.

Colombian artist Carlos Caicedo, meanwhile, explores Picasso’s work through photography in his “Imitando a Picasso” by using light to make it seem as if a real man and ox are casting Picasso-esque shadows on the ground. The effect is a marriage of the real world with the mind of Picasso.

Some of the conversations between the featured artists and Picasso do seem, admittedly, more indirect. Cuban painter Amelia Pelaez’s “The Waiting Lady” and Uruguayan artist Carlos Paez Vilaró’s “Rodoviario Saltimbanqui” both clearly draw from cubism and other styles associated with Picasso, but also pull from many other inspirations. Palaez’s painting, for instance, features bright, vivid colors inspired by art in Cuba in the early 20th century.

Perhaps the least obvious connection, despite its name, is Argentine artist Alicia Orlandi’s “Canto-Monumento a Pablo Picasso,” an optical illusion-style work that, interestingly, is placed in a space outside the room, where a visitor likely won’t see it until they leave the exhibition. In that sense, it is the final stop in Picasso’s influence.

That influence, this exhibition makes clear, was not simply in style and composition but also in how artists approach their work, and as a result, how their work reflects the world. In the oeuvre of these Latin American and Caribbean artists, the outsized impact of Picasso can be seen but perhaps not fully understood.

What A Dialog With the Americas seems to be missing is context. This collection raises — but doesn’t address — interesting questions of how Picasso’s influence reached the Americas and what made the dialogue with his work different in that region than in the rest of the world. How did these artists and their peers view Picasso and his work? How is that reflected in the work?

Inclusion of that context could take what is a small exhibition — in terms of literal size and thematic scope — to the next step of truly reflecting on an artist with such an enormous impact, on art and culture writ large, 50 years after his death.

No Comments