By Olivia Kozlevcar

This article was first published on October 4, 2022 in Washington Independent Review of Books here.

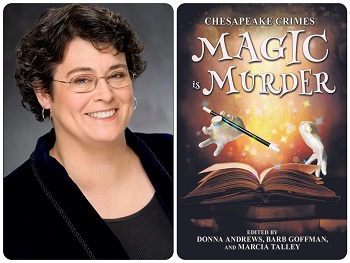

Magic Is Murder, a new story collection sourced from the talented members of the Chesapeake Chapter of Sisters in Crime (SinC), offers a thrilling, modern blend of mystery and the supernatural. Here, Donna Andrews, one of the anthology’s editors, shares a peek at the collection and the people behind it.

As you and your colleagues mention in your editors’ note, the overarching theme of the anthology is crime. What drove you in this direction?

What drove us was that we’re all crime writers. Magic Is Murder is the latest in a series that the editors — Barb Goffman, Marcia Talley, and I — have done to showcase the wealth of writing talent in the Chesapeake Chapter of Sisters in Crime. SinC is an organization founded in 1986 by a group of women crime writers who wanted to combat misogyny in publishing. They saw that women were at least half the readers in the mystery genre, but women weren’t getting half of the publishing contracts — and when they were published, they weren’t paid as much as male writers and didn’t receive as many reviews or award nominations. So they set out to level the playing field.

Marcia, Barb, and I are all longtime SinC members — in fact, Marcia is a past president of SinC National, Barb and I are both past chapter presidents, and we’re all three still active in the chapter. Although the anthology isn’t an official chapter publication, we limit submissions to chapter members, and we donate to the chapter any royalties generated after the publisher pays the contributors.

It’s been a rewarding project. Over the years, quite a few writers have had their first professional publication in the anthology series, including several who have gone on to thriving careers in publishing. We like to think that it’s a good opportunity for relatively new writers, appearing beside more established authors in a successful anthology series — successful and award-winning. Stories from the first nine volumes in the series have won the Agatha, Anthony, Derringer, and Macavity awards — in fact, a total of eight awards and 20 additional nominations. In short, the anthologies have done pretty well so far, and we like to keep building on that.

The collection also combines the dual themes of magic and murder. Why this subgenre?

We like to choose a theme for each anthology — past volumes have included Invitation to Murder (stories must involve an invitation); Fur, Feathers, and Felonies (stories must involve an animal); and Storm Warning (stories must involve the weather). Wildside Press, our publisher since the third volume in the series, likes the thematic approach — it definitely helps give each book a distinctive identity, which helps with sales and marketing. We editors think having a different theme for each anthology helps spark our contributors’ imagination. And we hope it’s fun for the reader, seeing the wonderful variety you can get when you turn a bunch of very different writers loose on the same theme.

When we chose magic and murder as the theme for the latest anthology, we did so because we know that these days, genre-blending is very popular. There was a time when many mystery readers disapproved of crime stories that involved magic or the supernatural, but today they’re one of the bestselling subgenres in the field. And we were also hoping to get a few crossover sales from fantasy readers.

Why is this collection meaningful to you?

Apart from the fact that having a book out never gets old, Magic Is Murder represents a milestone. Our team has been putting out an anthology every two years, and this is the 10th volume in the series. And yes, we only do this every two years because we like to give our contributors plenty of time to create and polish their stories — and give ourselves plenty of time to do the editorial and pre-publication work, because we do this as volunteers on top of our own busy careers in crime writing. So, the release of this volume marks two decades of working to shine a light on the talented writers of our local chapter — and producing anthologies that we are proud to present to mystery readers.

Now that the anthology is out, what’s next?

We’re already hard at work on the next volume, Three Strikes — You’re Dead! All the stories in that volume will feature sports. And we’re also pretty busy with our own writing careers. Barb is highly in demand as a freelance developmental editor on top of her career as a multiple-award-winning short-story writer — her work has appeared in Alfred Hitchcock’s Mystery Magazine, Ellery Queen’s Mystery Magazine, and dozens of anthologies. Marcia is also a prolific short-story writer, and Severn House recently released Disco Dead, the 19th book in her Hannah Ives mystery series. And I’m currently working on what will be the 33rd book in my Meg Langslow series — number 31, Round Up the Usual Peacocks, came out in August, and number 32, Dashing Through the Snowbirds, will be out in October. In short, what’s next for all of us is a lot more crime…but only on paper.

[Editor’s note: This article was written with support from the DC Arts Writing Fellowship, a project of the nonprofit Day Eight.]

Olivia Kozlevcar is an undergraduate at American University who dreams of pursuing law. She is currently the Life managing editor of the American University Eagle, as well as one of the hosts of its podcast, District of Cinema. Follow her online at @oliviakozlevcar.