By Gabriella Soto

This article was first published in DC Theater Arts here.

ArtsCentric has streamed their first feature-length film production, Jason Robert Brown’s musical The Last Five Years, starring Ryan Burke and Awa Sal Secka in transformative performances that subvert and surpass expectations. Director Kevin S. McAllister takes an unconventional cinematic look at the story with the help of Musical Director Cedric D. Lyles and dynamic choreography from Shalyce Hemby. The plot follows a young couple through their five-year relationship in specific moments that jump through time and eventually come full circle in a heartbreaking conclusion. To anyone who has ever fallen in love, stayed in love, and learned the sacrifices it takes to make love last, this one’s for you.

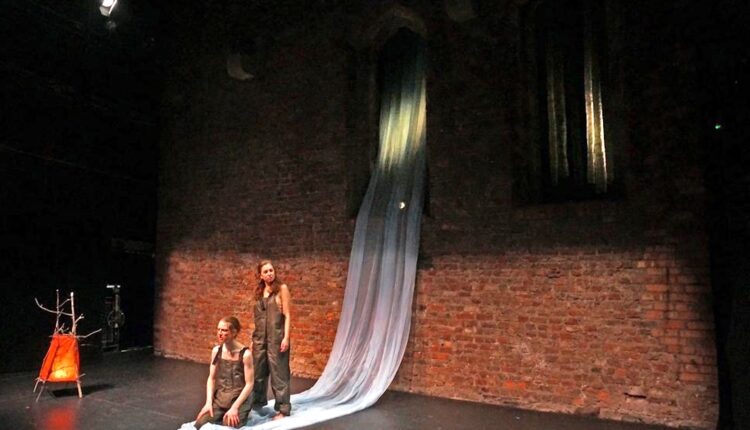

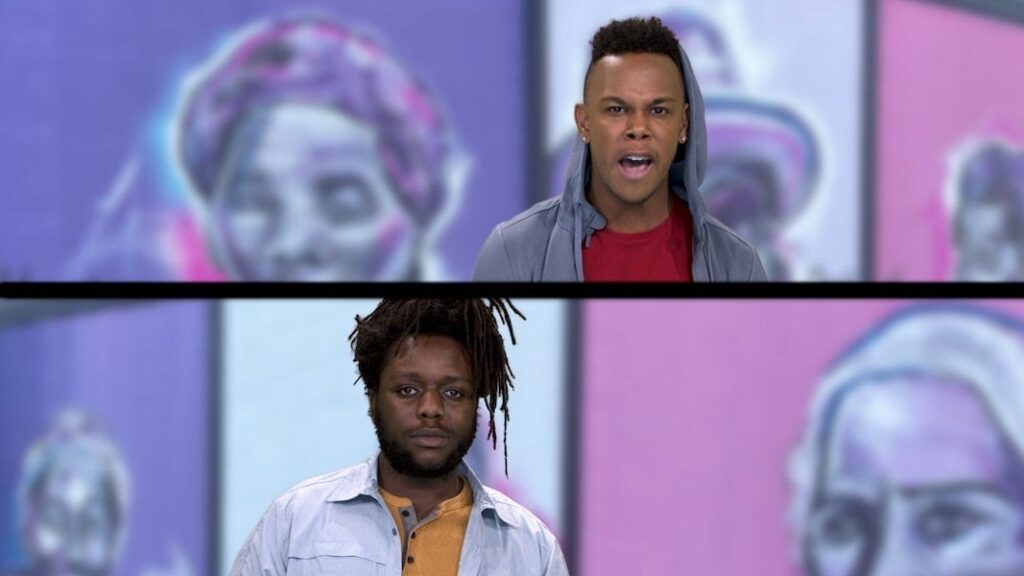

The show opens on a distraught Cathy played by Secka, in her gut-wrenching rendition of “Still Hurting.” The song follows her, alone in her darkened apartment, as she mourns the loss of her relationship with her husband, Jamie. Throughout the scene are swift cutaways to clips of the couple from memories past, then the film jumps into the next big number, “Shiksa Goddess.” Here audiences are introduced to the other main character, Jamie, through the animated vocal stylings of Ryan Burke. This quick shift in tone is a thrilling wake-up call to a happier time, sweeping audiences into different scenes as a true live musical would. Through masterful casting and direction, ArtsCentric has achieved a compelling theater experience with all the depth, diversity, and raw talent that could be expected of a Hollywood production.

The story is shot in a way that gives audiences multiple insights into the characters’ love story every step of the way as we view both sides through the perspectives sung by Jamie and Cathy in each of their respective songs. Cathy’s perspective is reflective, traveling backward in time, while Jamie’s moves forward, to a future Cathy already knows. Their monologues are delivered through lively musical numbers that carry the plot along at a steady pace with stellar performances from both actors, showcasing Secka’s wide range and belting abilities along with Burke’s impressive vocals, which bear an uncanny resemblance to Jeremy Jordan’s in the original cast recording. The talent and magnetic chemistry these two actors bring to their characters on screen is a hypnotizing thrill to watch.

Expressed in their story is the age-old battle between romance and career: How long can a partnership that’s supposed to be equal thrive when one person is flying high and the other is down on their luck? And what sacrifices are necessary to create our own version of happiness? Cathy is a struggling actress and Jamie is a successful author. As enticing as it is to watch these characters fall in love, we witness the harsh realities of the balancing act between managing a career, whether successful or failing, over your relationship. Feeling as though you should shrink yourself down, or that you will never reach up to the level your partner is at, remains the overarching conflict between them.

Both Cathy and Jamie are unfulfilled in some aspect of their lives. Their story of trying to make their marriage work, while in the midst of a major power imbalance, is a valid portrayal of why some things just aren’t meant to be. They both require the other to be something they are not. Jamie expects Cathy to play the “supporting wife” to his overwhelming success as a published young author while her own career hangs by a thread. Jamie has more expectations, obligations, and people relying on him than ever before, and yet he feels he is never able to truly enjoy his speedy rise to the top due to his wife’s struggle to flourish and overcome the constant setbacks in her own career.

Meanwhile, we witness Cathy feel constantly overlooked, brushed aside, and forgotten. She brings Jamie down by her own self-doubt, insecurities, and jealousy sprung from living in his shadow. Jamie brings her down by becoming so engrossed in his newfound fame and fortune that he is no longer able to be the attentive, faithful man she married. Both characters are similarly pursuing their artistic dreams, but at varying stages, showing a clear picture of what it means to be in different places at different times, and how this can affect those who come into our lives..

Director Kevin McAllister makes conscious efforts throughout to put his own spin on the piece with diverse casting and cinematography that pulls viewers in and keeps its audience thoroughly invested. An example is the creative visuals added to “The Schmuel Song.” Sung by Ryan Burke, it shows Jamie’s attempt to cheer up Cathy with a lighthearted holiday story. Here McAllister adds his own unique interpretation of the number by including in the scene cartoon footage of the characters Jamie is singing about. McAllister’s bold choice to have audiences not only hear the story but see it unfold on screen adds an entirely new element to the number and allows audiences to experience the story of Schmuel along with the characters telling it.

McAllister skillfully utilizes meticulous camera work as a lens to show the inner thoughts of the main characters in their quiet moments, revealing a level of depth in their psyche beyond what they tell us in song. A key moment of this is when Cathy comes home from her audition, having just performed “Climbing Uphill.” In one of the few moments of spoken dialogue in the show, Jamie recites to Cathy some of the story he is currently writing, and although she remains silent, we are able to get into the pain and hurt in her mind. We are jolted back and forth through quick flashbacks of her previous performance, where she sings about trying to make it as an actress and the grueling process of constant rejection, struggling to support herself while living in Jamie’s shadow. In between these flashbacks are frequent cuts to closeups of her face in the present scene, showing only the expression in her eyes. It is telling in this moment that there is no closeup on her mouth, because she feels voiceless, only sharing her deepest thoughts with us through a look in her eyes, and the imagery running circles in her mind.

ArtsCentric’s adaptation of The Last Five Years meets the challenge of converting a musical into film, beautifully transforming the story using the fundamentals of cinema, and proves that with a clear vision and team of dedicated talent, true art can be made.

ArtsCentric’s filmed production of The Last Five Years streamed on-demand from February 18 to March 3, 2022.